It amazes me that there is only one woman composer represented in the entire Suzuki piano repertoire—Theodora Dutton, who wrote Christmas-Day Secrets from Suzuki Piano Book One. When I point it out to my students, they want to know more. When I began to dig deeper, I discovered the captivating and sometimes touching story of how a young woman from Massachusetts in the Victorian Era set out to become a composer, and how her first publication was preserved for sixty-four years in Japan until Suzuki Piano brought it back to students around the world.

Theodora Dutton (Blanche Ray Alden) ca. 1916 (Cooke 1920).

Theodora Dutton (Blanche Ray Alden)

Christmas-Day Secrets was composed by Theodora Dutton, a pen name adopted by Blanche Ray Alden. Blanche was born in 1870 in Springfield, Massachusetts, the youngest of four daughters of Eliza Dutton and Philomen Alden. Shortly after her birth, the family moved in with Philomen’s sister, Helen, and her husband, George Washington Ray (Alden 1880). George owned a factory that manufactured paper shirt collars (Biographical Review Publishing Co. 1895) and Philomen worked with him. Helen and George had no children of their own and lived in a large Victorian home in a prosperous neighborhood in downtown Springfield. Blanche’s early works are placed in idyllic settings—a happy home, gardens, boating, or ice-skating—leaving the impression that she knew many delightful times as a child.

Main Street Springfield, MA in the 1890’s. Courtesy of the Archives of the Wood Museum of Springfield History, Springfield, MA.

Blanche’s mother was an accomplished vocalist and pianist and was her first piano teacher. Blanche loved to improvise at the piano (Dutton 1922). Her further musical instruction was entrusted to Louis Coenen (Dutton 1922), a violinist, pianist, vocalist, conductor, and composer who came from a well-known musical family in Holland. Coenen became the leader of a popular music group called the Orpheus Club (Springfield Republican 1903, 8) and was credited with elevating the level of music instruction and performance in Springfield. Blanche also studied counterpoint with E. Cutter in Boston and may have had instruction with other teachers in New York City (Dutton 1922).

Louis Coenen, Blanche Ray Alden’s second music instructor. (Springfield Biographical Clipping File, Courtesy of the Archives of the Wood Museum of Springfield History, Springfield, MA.)

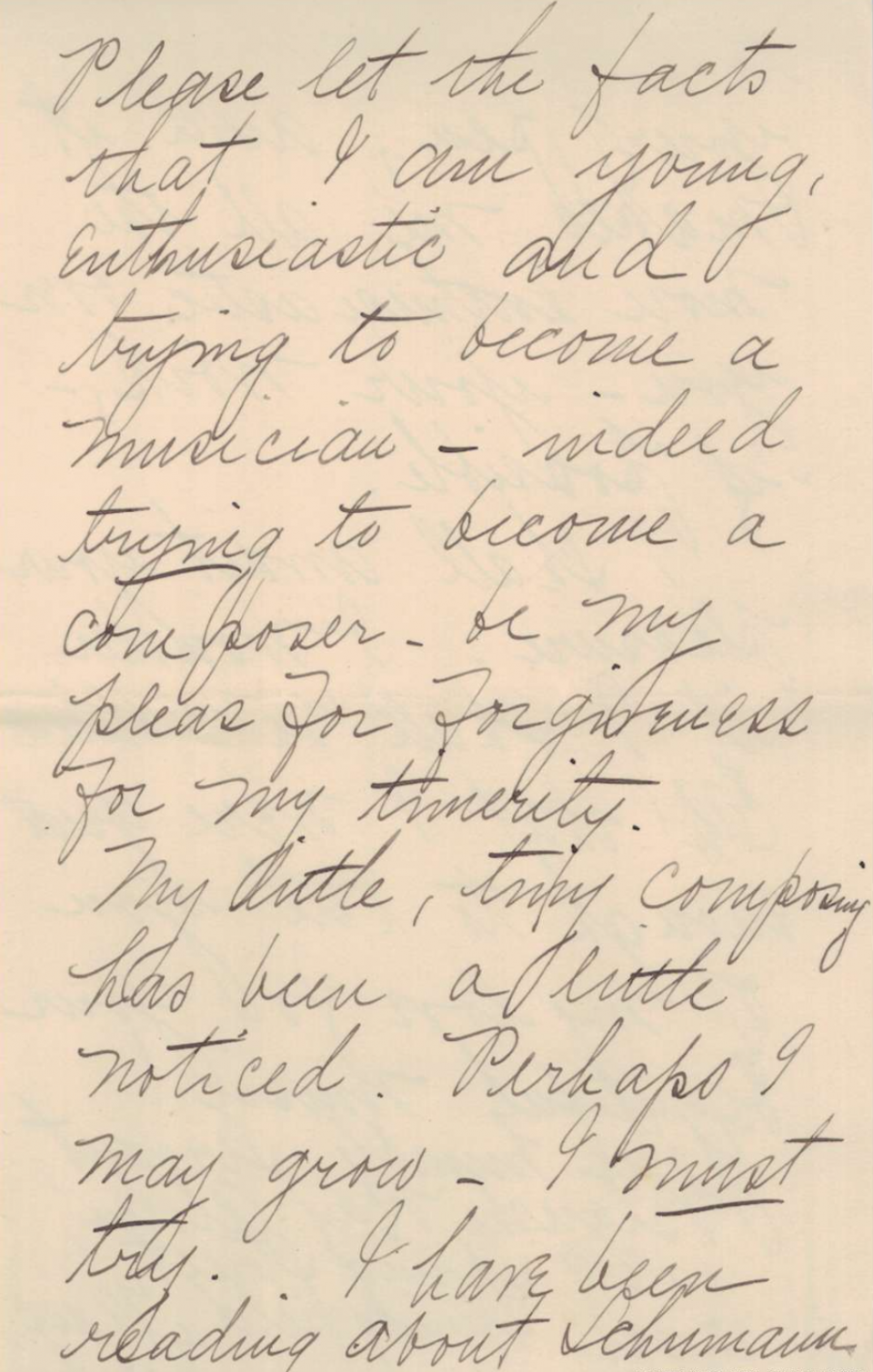

Blanche set her sights on a career in composing. She was twenty-three when her vocal composition, “Jerusalem,” was performed in her hometown (Springfield Republican 1893). A year later, she wrote to Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg (Alden 1894), saying, “I am young, enthusiastic, and trying to become a musician—indeed trying to become a composer…my little, tiny composing has been a little noticed. Perhaps I may grow—I must try…I wonder if I shall be noticed.”

Excerpt from Blanche Ray Alden’s letter to Edvard Grieg (Alden 1894).

Blanche became the music instructor at Springfield’s French-American College (now the American International College) when she was 25. Piano lessons were available to all students two times each week, for five dollars a term (Announcement of the French-American College 1896, 1897, 1898). Blanche collaborated with other faculty to produce recitals that were open to the community (Springfield Republican 1896, 8) and may have been working on her early compositions during the same time period.

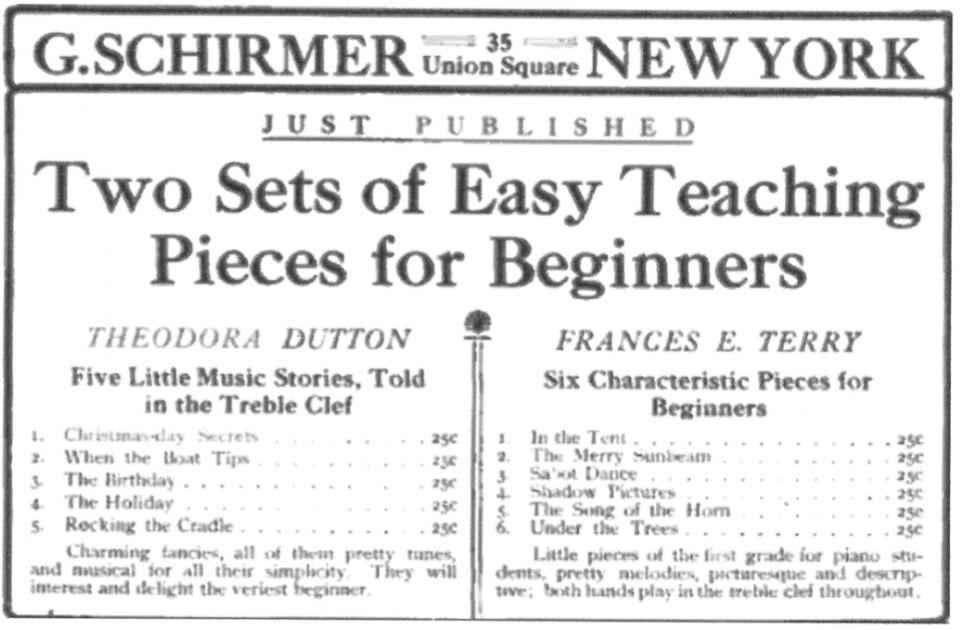

By 1905, all four Alden sisters lived in New York, and Blanche seemed to have transformed her life. She lived in Greenwich Village with another piano instructor from Springfield, Frances E. Terry (Alden and Terry, 1905). Blanche also adopted the pen name, Theodora Dutton. She and Frances each published sets of piano pieces for children in 1906. Christmas-Day Secrets is listed first in her set (Baltzell 1907).

An early advertisement for Christmas-Day Secrets, with Theodora Dutton and Frances E. Terry’s compositions advertised together (Baltzell 1907).

Even while she began composing as Theodora Dutton, Blanche used her real name to author an interview with opera singer Emma Eames (Alden 1906). She attributes these words to Emma Eames; however, they speak as though they came from Blanche herself: “above all these things become your own possessor…Make your mind master of the situation before you give reign to your imagination. In other words, learn your psychic and musical technique, keep your heart single and work!” True to this advice, she remained single and published around 100 pieces between 1906 and 1927.

Blanche’s choice of the pen name Theodora Dutton gives insight into her strong character. Theodora was a historical figure who rose from servitude as an actress to become a powerful Roman Empress. Blanche also honored her mother by choosing to use her maiden name, Alden. Living in an era that welcomed female performers but frowned on them composing, some women composers used a male pseudonym to hide their gender. She chose a female name, thus taking a stand to reform the system, rather than conform to it. A female pseudonym also allowed her to market her pieces by performing them at teacher workshops (Borroff 1975).

In her time, Theodora Dutton was recognized as an important composer and excellent piano instructor. She was featured as “A Favorite Composer” (Cooke 1936) in The Etude Music Magazine and another article said her compositions “combine melodic charm with true musicianship,” and are “pieces of lasting educational value” (Orem 1916). Her violin (Bloom 1927) and piano (Cooke 1919) compositions were counted among the best of woman composers and she noted that opera singer Ernestine Schumann-Heink was to debut a set of her vocal pieces (The Post-Star 1913). Her piano compositions were even called some of the best to accompany silent movies (Rapee 1924, Silent Film and Music Archive 2016). If you are looking for good beginner/intermediate Romantic Era pieces by a woman composer, think Theodora Dutton!

By 1931, she had retired to Northampton, Massachusetts to live with her sister, Helen, and Helen’s husband, in a Victorian home just blocks from Smith College (Northampton, MA City Directory 1931). She passed away in 1934 and is buried with her family in Springfield Cemetery. Just a family headstone engraved “Ray-Alden” marks the place. Today, her music stands as her only monument.

Christmas-Day Secrets

Christmas-Day Secrets is the first Romantic Era selection in the Suzuki Piano books and builds on the earlier Book One pieces to prepare students for more advanced repertoire. I asked a panel of piano instructors (Teachers’ Panel 2021) to describe the unique features and techniques in Christmas-Day Secrets, and I organized their responses in the following table.

Theodora Dutton’s pieces always have a story to tell, and each teacher had their own spin on the story. The story that my students love comes in part from Mary Craig Powell (Powell 1993). It’s about two children, one outgoing and the other quieter, peeking into the room that holds their presents. They open them in the B section and enjoy the happy memory in the reprisal. From the opening bar, the rests breathe life into the duple time signature, and the motifs create a rolling momentum that is also characteristic of her work. Often the first line is played forte to contrast with the piano repeat. You feel the influence of a violinist in the piece, which is entirely in treble clef. Christmas-Day Secrets is the first Suzuki Piano piece in a full ternary form and is a charming piece for performance.

How Christmas-Day Secrets came to be included in the Suzuki repertoire

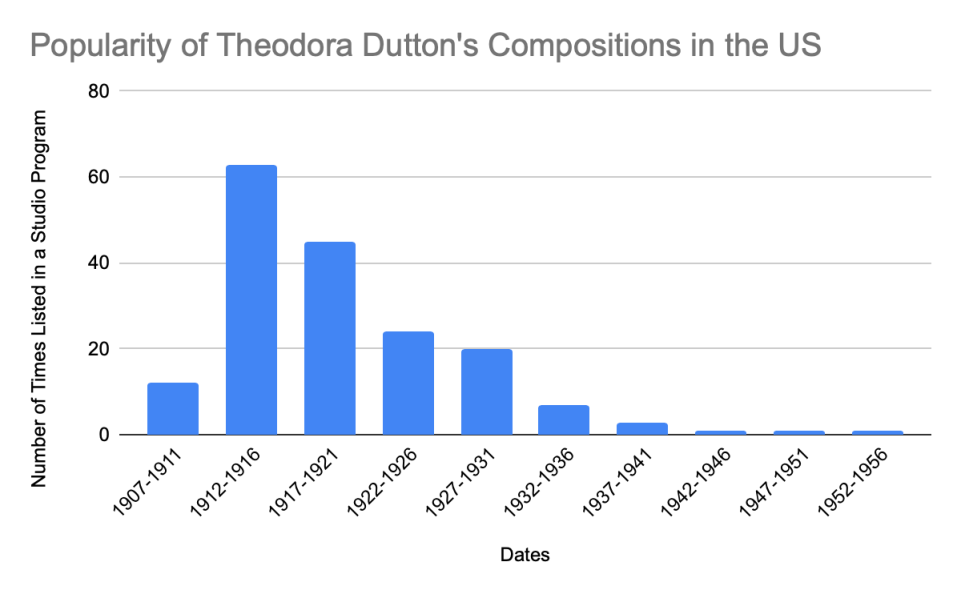

It was a bit of a mystery how Christmas-Day Secrets came to be included in the Suzuki repertoire since it had been out of print for six decades by then. My first step toward finding an answer was to understand the availability of her works. In the early 1900’s, music teachers would often publish their studio concert pieces in their local newspaper, so I searched “Theodora Dutton” in two archives of United States newspapers (Ancestry.com, GenealogyBank.com 1900-2021). Her pieces were counted 177 times among studio concerts in the United States, but Christmas-Day Secrets only appeared once, in the 1911 Colorado Springs studio of Miss Daisy Thompson. The peak years for her music to appear were 1912-1916, and I wasn’t able to locate any copy of Christmas-Day Secrets outside the Suzuki Piano Books.

The popularity of Theodora Dutton’s compositions in the United States over time, based on newspaper archives (Ancestry.com, GenealogyBank.com 1900-2021).

Christmas-Day Secrets was published during the Meiji Era of westernization in Japan, which was a turbulent time of modernization (Howe 1993/1994, Gaspar 2014). Hundreds of students traveled to the United States and Europe for their education, and western teachers and missionaries also traveled to Japan. Young people were educated at home and abroad. Western music flourished in Tokyo, and the piano became a symbol of the modern Japanese household. When the Meiji Era came to an end, westernization fell into disfavor, but western music remained popular (Gaspar 2014). It appears that Christmas-Day Secrets made its way to Tokyo in the Meiji Era and was played primarily in Japan for years.

The trail of facts leads to one of the founders of the Suzuki Piano Method, Mrs. Shizuko Suzuki (Suzuki 1977 and 1994). In 1936, she became Dr. Suzuki’s accompanist at the Imperial Music School in Tokyo, and she later married his brother, Kikuo. She and her three-year-old daughter were among the millions of Japanese civilians who fled the Allied bombing of Tokyo in 1945. I wonder what, if any, sheet music she could bring with her.

Shizuko Suzuki became the first Suzuki Piano instructor later in 1945 in post-war Kiso-Fukushima. Dr. Suzuki, who lived next door, suggested she begin by selecting the repertoire. When he started his school in Matsumoto the next year, she commuted weekly to accompany him and developed Suzuki Piano further. She moved back to Tokyo in 1958 and said that Dr. Suzuki came there in 1969 to help select the repertoire for Books One and Two. Three other female piano teachers, Haruko Kataoka, Ayako Aoki, and Keiko Sato also contributed to Books Three and on (Suzuki 1977 and 1994). Since Shizuko Suzuki was the first to teach Suzuki piano, and since she also selected the Book One repertoire with Dr. Suzuki, it’s apparent that she was instrumental in bringing Christmas-Day Secrets and Theodora Dutton back to the modern repertoire.

Part of the puzzle is why Christmas-Day Secrets is credited only to “T. Dutton (dates unknown)” in Suzuki Piano Book One. One hypothesis is that using only the composer’s first initial was an attempt to obscure that the composer was female (Lazarus 2020), however, this theory doesn’t account for why the dates are also missing. My alternative hypothesis is that they were working from an old, illegible copy or a translation/transcription, since it was reprinted six decades after its initial publication and survived a wartime evacuation. It’s even possible that Shizuko Suzuki wasn’t able to bring the sheet music with her when they fled Tokyo and relied on her memory alone.

Shizuko Suzuki teachingat Piano Summer Camp, 1990. Courtesy of theTalent Education Research Institute, Matsumoto, Japan.

Whatever the reason her full name is missing, it’s time to give credit where it is due! Teachers, please write in “Theodora Dutton (1870-1934)” for the composer on your copy of Christmas-Day Secrets and share this story with your students. We should also recognize the contributions of Shizuko Suzuki and the other teachers. The next printing of the Suzuki Piano Book One should acknowledge Theodora Dutton and Shizuko Suzuki. The contribution of these fascinating women is a vital part of the Suzuki Piano legacy.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to these insightful and knowledgeable professionals, who helped uncover the facts about the life of Blanche Ray Alden: Margaret Humberston, Curator of Library & Archives, Wood Museum of Springfield History, Springfield, Massachusetts; Martin Cleaver, Technical Services Librarian, Shea Memorial Library, American International College, Springfield, Massachusetts; Timothy Sestrick, Music Librarian and Hunter King, Music Library Technician, Presser Music Library, West Chester University, West Chester, Pennsylvania; Michele Kehoe, Office Manager, Springfield (Massachusetts) Cemetery; Dennis Kountz.

References

Cooke, James F., ed. 1920. “Two Recent Etude Prize Winners.” The Etude. Presser’s Musical Magazine 38, no. 3 (March): 166. https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/666.

Alden, Blanche. 1880 United States Federal Census. Springfield, Hampden, Massachusetts; Roll: 536; Page: 178C; Enumeration District: 315.https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6742/images/4241713-00360?pId=43899171.

Biographical Review of the Leading Citizens of Hampden County, Massachusetts. 1895. Boston: Biographical Review Publishing Company.

Dutton, Theodora. 1922. Fireside Stories: An Adventure. New York, NY: G. Schirmer, Inc.

Springfield Republican. 1903. “Early Days of the Orpheus Club.” May 31, 1903. https://www.genealogybank.com/doc/newspapers/image/v2%3A11BC3DF3E61E32B5%40GB3NEWS-11E098E7B69553E0%402416266-11E098E80965CAD0%407.

Springfield Republican. 1893. December 23, 1893. https://www.genealogybank.com/doc/newspapers/image/v2%3A11BC3DF3E61E32B5%40GB3NEWS-120143DE13D9C1B0%402412821-120143DE592EB760%405.

Alden, Blanche Ray. 1894. “Scanned copy of letter Blanche Ray Alden wrote to Edvard Grieg in 1894.” Bergen Offentlige Bibliotek. Accessed July 30, 2021. http://www.bergen.folkebibl.no/arkiv/grieg/brev_tilknyttpost/stor_fabr001.pdf.

Announcement of the French-American College for 1895-1896, 1896-1897, 1897-1898. 1896, 1897, 1898. Springfield, MA: French-American College.

Springfield Republican. 1896. April 28, 1896.

Alden, Blanche and Terry, Effie. 1905 New York, U.S., State Census. Manhattan, New York; Election District: A.D. 05 E.D. 14, page 12. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7364/images/004518302_00338?pId=526529.

Baltzell, Winton J., ed. 1907. “Two Sets of Easy Teaching Sets for Beginners.” The Etude, Presser’s Music Magazine 25, no. 4 (April): 212. https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/524.

Alden, Blanche R. 1906. “Emma Eames’ Advice to the Girl with a Voice.” Sunday Plain Dealer (Cleveland), March 25, 1906, 8.

Borroff, Edith. 1975. “Women Composers: Reminiscence and History.” College Music Symposium, (October). https://symposium.music.org/index.php/15/item/1733-women-composers-reminiscence-and-history.

Cooke, James F., ed. 1936. “A Favorite Composer.” The Etude, Presser’s Musical Magazine 54, no. 3 (March): 191. https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/842.

Orem, Preston W. 1916. “Educational Notes on ‘Etude’ Music.” Edited by James Francis Cooke. The Etude, Presser’s Musical Magazine 34, no. 6 (June): 422. https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/625.

Bloom, Clifford. 1927. “An Excellent Program of Compositions by American Women.” Edited by James F. Cooke. The Etude, Presser’s Musical Magazine 45, no. 3 (March): 184. https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/743.

Cooke, James F., ed. 1919. “Album of Compositions by Woman Composers.” The Etude, Presser’s Musical Magazine 34, no. 6 (June): 334. https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/658.

The Post-Star. 1913. “Rare Treat for Members of Class.” June 9, 1913, 5.

https://www.newspapers.com/clip/79603087/theodora-dutton-concerttraining-event-i/.

Rapee, Erno. 1924. Motion Picture Moods. New York, NY: G. Schirmer. http://www.sfsma.org/ARK/22915/motion-picture-moods/.

Silent Film and Music Archive. 2016. “SFSMA Recording Project Wins Society for American Music Sight and Sound Subvention.”. https://www.sfsma.org/ARK/22915/sfsma-recording-project-wins-society-for-american-music-sight-and-sound-subvention/.

Teachers’ Panel. 2021. Fay Adams, Bruce Anderson, Jane Armstrong, Jennifer Nicole Campbell, Gail Lange, Jean Kountz, Joan Krzywicki, Rebekah Waggoner, and Kerri Williams. Private communications.

Powell, Mary C. 1993. Focus on Suzuki Piano: Creative and Effective Ideas for Teachers and Parents. Van Nuys, CA: Alfred Music.

Kataoka, Haruko. 1996. How to Teach Beginners. Edited by Karen Hagberg. Translated by Mitsuo Furumachi. Bellingham, WA: Suzuki Piano Basics Foundation.

GenealogyBank.com. 1900-2021. Newspaper archives search “Theodora Dutton.” Accessed June 24, 2021.

Ancestry.com. 1900-2021. Newspaper archives search “Theodora Dutton.” Accessed June 24, 2021.

. “Women Music Educators in Japan during the Meiji Period.” The 14th International Society for Music Education: ISME Research Seminar, no. 119 (Winter), 101-109.

Gaspar, Veronica. 2014. “History of a Cultural Conquest: The Piano in Japan.” Acta Asiatica Varsoviensia, no. 27, 83-99.

Suzuki, Shizuko. 1977. “The Beginnings of the Suzuki Piano Method.” American Suzuki Journal, no. 26.1 (November), 35.

Suzuki, Shizuko. 1994. “The Beginnings of the Suzuki Piano Method.” International Suzuki Journal 5, no. 2 (Fall): 8-9. https://internationalsuzuki.org/journal/ISA-Journal-5-2.pdf.

Lazarus, Penny. 2020. “Becoming Weavers: Piano Students and Their Commissioned Arrangements of Music by Under-Represented Women Composers.” Piano Magazine 12 (5): 36-42.

Northampton, Massachusetts, City Directory. 1931. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2469/images/10102719?pId=507977711

**