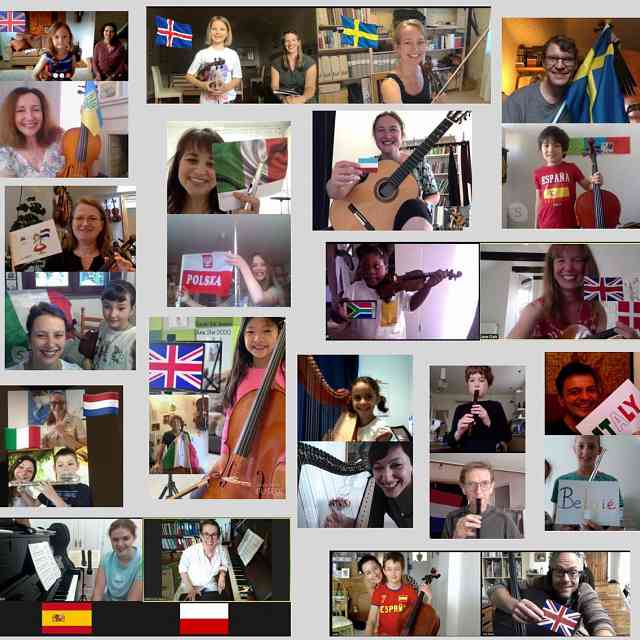

For two weeks this summer, I taught two classes (one for adults and one for families) on Black classical composers and musicians. It was my way of bringing hope and sharing historical knowledge while the protests of the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor took place in this country and around the world. Plus, this pandemic kept me stationary for far too long. I got tired of being angry, depressed, and feeling helpless. Because I taught this class last October to homeschooling students, I did not know what to expect this time around. Would people be open to this subject? Would I be adding fuel to the already burning fires of racial frustrations? Imagine my surprise when 26 families and 56 adults (including a Juilliard faculty member) signed up for my class.

I started the violin at age three with the Suzuki Violin Method, and having spent most of my musical life being the only violinist of African descent and later being one of the few is something I still have not gotten used to. It truly does not feel normal to me. I knew in my heart of hearts that there were more musicians who looked like me in this field. I have met them, talked to them, performed with them, encouraged them, and supported them. But when I am sitting in my local orchestra, I am the only tenured musician—again. During my class, very few teachers, music directors, conductors, parents knew of any Black classical musicians either. When I asked them why they chose me as their teacher, a student simply stated, “I wanted to hear this history from a Black person; a Black woman.” Her statement affirmed me in areas of my soul I did not even think needed to be affirmed. I had gotten so used to being invisible; that pivotal moment showed me my presence mattered. My voice mattered.

Before it seems like I just want to toot my own horn, let me explain further. My first orchestral experience started at the tender age of nine. I still remember like it was yesterday because one of the pieces on the program was Mozart’s Eine kleine Nachtmusik and I played the awesome harmonious and rhythmic second violin part. It is one of my favorite pieces to play to this day. And yet, in all my years as a violinist, teacher, symphony musician, freelancer, very few times have I been asked my perspective, opinion, expertise, or anything as it relates to classical music or even my cultural experience as a Black classical musician. I have two violin performance degrees from a highly reputable conservatory. I’ve learned the same repertoire as my counterparts, auditioned for orchestras and got in like my counterparts, I’ve sacrificed, I’ve worked hard, I have earned my place in this field and yet it was as if I was invisible. Did I have a lot to say? Of course! It eventually got to a point where I just sat back and chose to focus on the music. Isn’t that what this was about anyway? The music?

One of the students who took my Black classical composers and musicians class is a 14-year old violinist of African descent. Because she was the youngest student in the adult class, she was asked about her experiences being in her local youth symphony orchestra. She shared how kids made fun of her hair, saying it was too big. She felt lonely and did not feel she belonged. She felt her friends did not understand her love for classical music although she would take time to educate them about it. A beautiful moment occurred when the adults shared words of encouragement. They affirmed her, told her she mattered in this field. Another student from the UK said, “One day another Black girl will see you onstage and will tell herself, “I can do this too!” Haven’t you ever loved something so much or been passionate about something but yet didn’t see the representation or felt your presence mattered, but once you did, it lit a fire in you like yes I am not alone? Did seeing that person also give you a sense of what is possible for you? Caused you to feel like you could climb a mountain, overcome any obstacle, or give you that “nothing is impossible for me” feeling? You may not have felt the sting that the lack of representation brings as it relates to your race or ethnicity, but maybe you have felt this sting because your passion of choice has led you to be part of a male-dominated field, or mostly abled bodied field or a field where having a learning challenge would cause you to stick out. Nobody should feel as if their presence does not matter or is not welcomed. We were created to matter, to belong, to feel a part of something that is bigger than us. This sense of community helps people have a deep sense of identity. Hopefully when a child—a Black child—sees me onstage, they will see themselves in me. As teachers and educators, it is our job to make sure children are seen and heard—every child—to the best of our ability.

During my class, I included a Living Legends feature where I highlight classical musicians and composers of African descent who are alive today and have chosen classical music as their career choice. Featured are musicians such as Anthony McGill, first Black principal clarinet of the New York Philharmonic, Joseph Conyers, associate principal bass of the Philadelphia Orchestra, and Monica Ellis, bassoonist and founding member of Grammy nominated wind quintet Imani Winds, just to name a few. These people are showing up to inspire, encourage, educate, and motivate change. We are here and our presence matters. We are not hiding. We have been here all along doing the exact same things you are doing.

Now is the time to be the change we want to be. To wait for change to happen naturally would only risk things remaining the same. We are where we are now, in terms of race relations in this country, because of some people wanting things to stay the same. The fight for equality is still an ongoing fight even in classical music, but it is a necessary one.

If you are a Suzuki teacher who is ready to be the change you want to see because you truly believe it is important for this generation of classical musicians and the next, here are five tips I shared with SAA member and violin teacher Ashley Rescot on her blog, Music Genes, about ways the classical music community can better integrate Black composers and musicians into our curriculum:

-

Educate yourself. Show an interest. There are more than 300 Black classical composers and musicians, both deceased and alive. Aim to do your own research.

-

Once you have educated yourself, make it a point to highlight the works of these musicians. Call your local classical music radio station and request that more music be heard from Black composers and musicians. Share the information with your colleagues, on your blog, your podcast, encourage your students to research these musicians. Come up with a project where you and your students can do research together. Start with a simple question such as, what Black composers and musicians were alive during the time of Mozart, Beethoven, or Brahms? Google is your friend. The beauty of researching history is that it can take you down many amazing paths of discovery. Make it fun for your students.

-

Get to know more Black classical musicians. Having relationships are breeding grounds for good conversations and opportunities for personal growth and development. It is also a great opportunity to gain a wealth of knowledge that you may not have had before.

-

If you are a member of a symphony orchestra, artistic director, orchestral librarian, personnel manager, or board member, go to your conductor or musician’s committee and offer recommendations for repertoire that highlight Black classical composers and invite Black solo artists to appear on your programs. For a great example of diverse programming, check out the Fall 2019 season of Music at the Gardner: https://www.gardnermuseum.org/sites/default/files/uploads/files/2019FallMusicCalendar.pdf

-

Wherever you purchase your sheet music, request repertoire from Black composers. Buy recordings that feature Black solo artists. I could go on and on, but the main point I am trying to make is that it will take effort and intentionality to integrate music from Black composers into the music community. It will not happen by default.

It was not until I was in undergraduate school that it occurred to me to research classical composers and musicians of African descent. That is roughly 15 years of my life where not one teacher or youth symphony conductor took the time to expose me to that information. Or expose other students, White or Black, to that information as well. At the same time, one does not know what one does not know. The first composer I found was William Grant Still. I performed his Suite for Violin and Piano in one of my recitals. That feeling of performing a piece by a man who was an integral part of the Harlem Renaissance, who attended the Oberlin Conservatory as well as the New England Conservatory gave me a deeper sense of accomplishment. I enjoy Beethoven, Mozart, and Tchaikovsky just like most people in this field, however my scope has been enriched and broadened by researching and studying the lives of Black classical composers and musicians. I can stand on their shoulders now because of the beautiful yet racially tumultuous path they paved for me. Their strength and courage inspire me, encourage me.

[pull quote]

We were created to matter, to belong, to feel a part of something that is bigger than us.