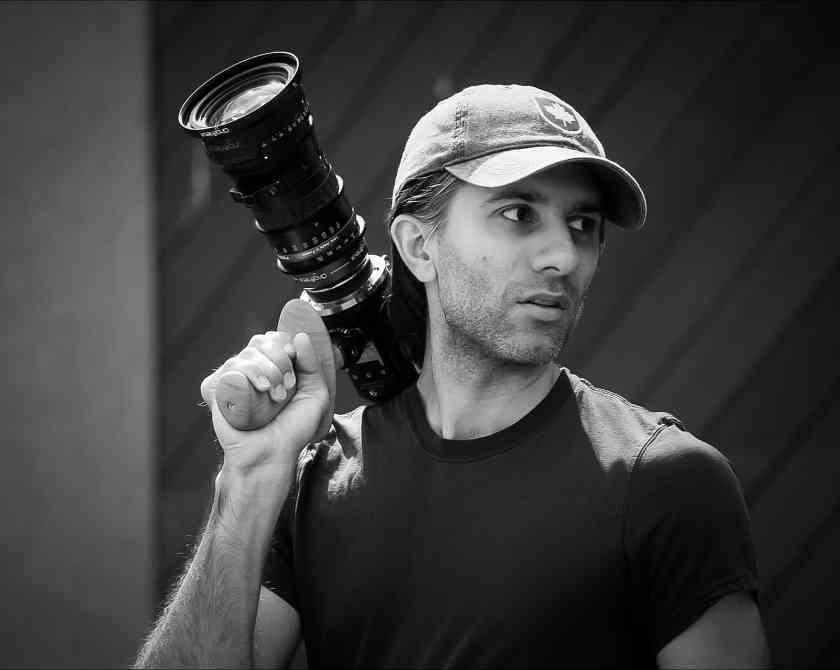

Cinematographer Benji Bakshi.

Suzuki pedagogy encompasses an entire world of ideas, thoughts, and disciplines. We have an array of areas of study, from violin to trumpet, Early Childhood Education to Suzuki in the Schools. Beyond musical study, Suzuki principles resonate with diverse disciplines such as developmental psychology, Montessori education, and family science. But could the Suzuki universe extend even farther? Could we find it if we “boldly go where no one has gone before”? Cinematographer Benji Bakshi believes so. As the Director of Photography of the new season of Star Trek: Strange New Worlds which aired on Paramount Plus over the summer, Bakshi richly showcases his “visual music” approach to filmmaking, drawing on his deep musical and Suzuki roots. His life and career show the enduring power of Suzuki principles and the musical spirit, and he serves as a reminder of Suzuki’s vision of not only producing stellar musicians, but more importantly, educating noble humans.

Bakshi’s environment was filled with music from the beginning. “Music was always in our household, which is an absolutely wonderful way to start,” said Susan Bakshi, Suzuki piano teacher and Benji’s mother. “Benji has an older brother who studied violin when he was four, so when Benji was two, he was coming to group class and miming all the bowings to the

music.” This immersive musical environment stretched back to Susan’s upbringing. Her mother was a pianist and Susan spent hours hearing the lessons her mother taught, eventually (and unintentionally) memorizing the students’ pieces. A similarly rich musical environment created an almost effortless pathway for Benji to begin playing. “I can’t remember a time when music wasn’t around me. I think that was inevitable that I was drawn to music—it was more like breathing,” recalls Benji.

He started with violin as a four-year-old, then switched to piano, but it was the cello that truly matched his character. “I liked the bigger intervals and being able to really sit on a note and have it fill the whole room,” he shared when we met for an interview, adding that the cello “looked like a violin, but I wanted to sit down!” He began his cello lessons at the age of nine with Alicia Randisi-Hooker and quickly took to the instrument.

On the third side of the Suzuki Triangle, Susan approached the complicated role of musician/parent with a thoughtful circumspection that was evident throughout our discussion. For her, it was important to “find the character of my own child, and find what was thrilling for them,” while recognizing that each child was different. “I thought I had it figured out with my first child until my second one came along—he’s a totally different animal!” she shared. During her Suzuki studies with Haruko Kataoka, Susan was impressed by her ability to teach advanced concepts to children in simple, digestible ways. Additionally, she marveled at the idea that “you don’t have to become a concert artist in order to take music lessons,” which led to her supportive, yet non-restrictive approach to guiding her own children into adulthood.

As Benji continued with music, he appreciated the growing kinship he felt with his peer musicians and began to enjoy the hard work of learning an instrument. Most of his best friends were similarly involved with music, and they developed a bond in their shared commitment to developing as musicians. The value of this commitment to working became clear when he thought about his friends who weren’t involved in music: “I felt like they were missing something because they didn’t have this process by which they learned to practice something. My friends who weren’t naturally good at something tended not to pursue things very deeply because they thought ‘Well, I hit the hard part and wasn’t any good at it’ instead of having the tools to practice it.” Music for him was something to be worked at, developed, and continually refined, an ethos that he’s brought to his career in filmmaking. Reflecting on his career in Hollywood, he notes that “in some ways, the world around me doesn’t have enough practicing,” as he finds that among the people he works with, the most skilled artists are the ones who “have the practice mentality.”

By the time he enrolled in college, Bakshi’s interest in film, a thread that began earlier in his youth, grew into a larger passion. His comfort in the musical-artistic environment enabled this exploration of new fields. He recalled being awestruck as a teenager by a documentary series “Movie Magic” that showed how movies were made, leading to his experiments playing with homemade, handheld cameras. This allowed him to learn in a low-stakes and exploratory way, much in the same way that a skilled Suzuki teacher can teach students advanced concepts through games in group class. It wasn’t until college that Bakshi learned the technical details of cinematography—and that there was even a specific role called “cinematographer.” He began to see many similarities between the musical and cinematographic processes, since both involved “a lot of practice, creativity, and collaboration. And you hold an instrument, and practice until you get better at it. Then, at the end of it, you have an audience, and if you did your job right, they enjoy it.”

A scene from the musical episode of Star Trek: Strange New Worlds (season two, episode nine).

So, what exactly does a cinematographer do? As Bakshi describes it, a cinematographer, also known as director of photography, “is essentially the one who’s responsible for shooting the footage. Cinematography is somewhat like still photography, but in motion and with other narrative instincts at play.” From a wider vantage point, Bakshi explains that “cinematography is the process of interpreting a story or a script and translating it into a motion picture format. Cinematographers need years of experience honing their narrative and visual instincts, learning the technical crafts of their tools, and managing crew and collaborating with larger creative teams.”

Bakshi views his transition from an early life in music to a career in cinematography as a lateral move: “Ultimately, music was the perspective on life that I had from the beginning, and it was my introduction to the creative process. My creative career began as a musician.” Cinematography allowed him to combine his strong interest in visual arts with music’s temporal and experiential qualities, but his musical instinct remains an essential thread in his work. “I still hold the ethic and creative process of music in everything I do, and to me, cinematography is visual music. That’s how much I think they’re interwoven: it’s basically the same process. I’m just creating a visual result,” he shared.

The principle of visual music comes into focus quite literally in Bakshi’s work on season two of Star Trek: Strange New Worlds. In it, Bakshi’s cinematography has a sense of lightness and effortlessness, something more like balletic choreography rather than technical filmmaking. It seems to perfectly capture both the feeling of being weightless in space and the overall optimistic character of the Star Trek world.

His musical roots are on full display in the season’s ninth episode, “Subspace Rhapsody.” It is, for the first time in the nearly sixty years of the Star Trek franchise, a musical. Yes, even Spock sings! What’s most impressive about this episode is not its novelty, but the opposite: the singing and musical elements materialize organically and never seem out of place or inauthentic. This is partly because musical sound is a plot element in the episode, but when you look closely, it’s clear that Bakshi’s fluid cinematography enables the musical numbers to integrate seamlessly into the story. To borrow Bakshi’s phrase, the music seemed evitable, “more like breathing.” Though I’m no Trekkie myself, I couldn’t help but be moved by the earnestness and honesty of the musical storytelling in this episode.

Outside of these surface musical connections, the entire Star Trek franchise shares a similar perspective with the Suzuki Method. Bakshi notes that the broader trend in entertainment has been toward dystopia and tragedy. “And the danger,” he continues, “is that if you fill people’s heads with this for almost a generation, that’s not necessarily what the world becomes, but it’s what everyone sees in the world.” Star Trek, on the other hand, has always maintained a “generally positive outlook, an upward belief and optimism,” and this was what attracted him to the project. His attraction makes perfect sense: in our conversation, both Benji and his mother lauded the Suzuki Method for its own positive belief, its way of approaching the world from a joyful and creative (rather than destructive) direction.

The musical and Suzuki worlds are still very much a part of Bakshi’s life. Cinematographers experience periods of intense work, with shoot days sometimes lasting twelve to sixteen hours. But after these busy periods, as Bakshi puts it, “you can afford to take some recuperation time,” which for him, meant exploring the cello in a new way. After finishing up shooting Strange New Worlds, he set out to learn the Bach Chaconne, drawing inspiration from the many online music communities that sprung up since the pandemic. It has opened a rewarding new world in his musical life.

And he’s recently been exploring yet another new musical world: becoming a Suzuki parent. His four-year-old son, Bodhi, is now a Suzuki piano student, continuing the family lineage. When introducing Twinkle Variation A, instead of using traditional syllables, Benji and Susan melded the child’s own name to the rhythm: “Bo-dhi, Bo-dhi, Bak—shi.” Along his remarkable journey, from group class observer to cellist to cinematographer and now Suzuki parent, Benji Bakshi continues to explore strange—and exciting—new worlds.