By Maggie Snyder

In 2018, I did a full survey of all the works performed at my home university in Athens, Georgia. Through this statistical data, I confirmed that the number of works written by women was grossly disproportionate to the number of works by men. Of 1,926 works performed, only 93 of them were by women composers: a grand total of 4.8%. While this was an increase from my study of the 2016–2017 school year that showed only a 2.75% proffering of woman-composed works, it was still a significant under-representation. I was determined to do what I could to effect significant change.

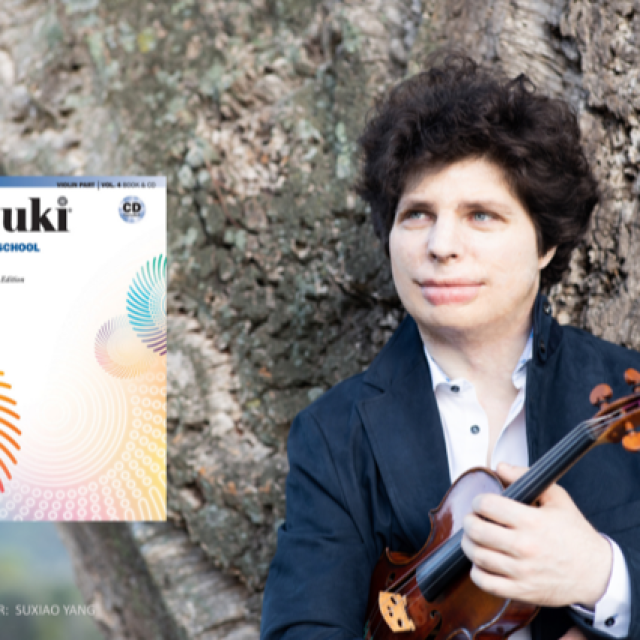

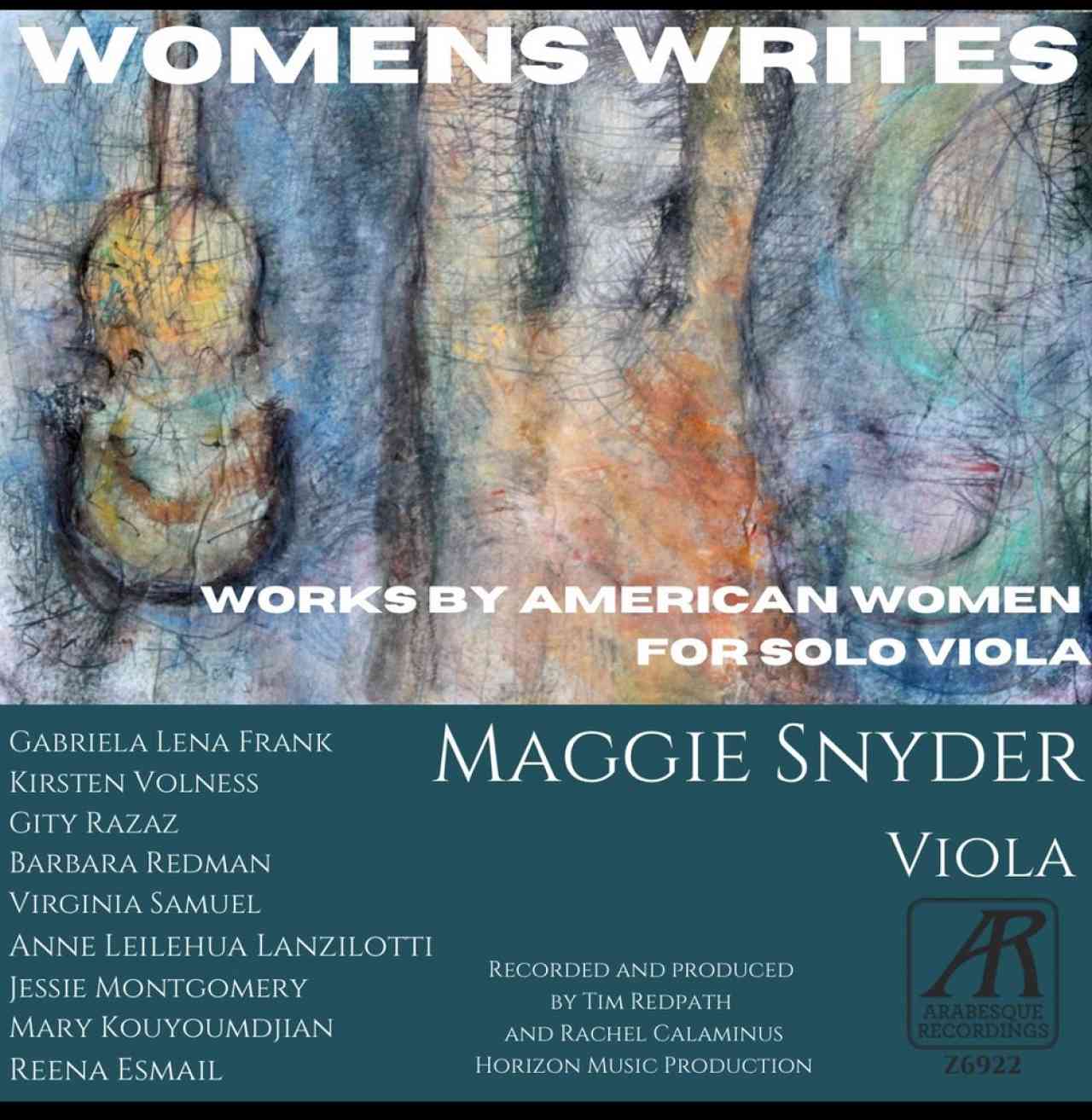

Figure 1. The cover of Maggie Synder’s recording, published by Arabesque Recordings.

These thoughts occurred simultaneously as I was also pondering the significance of the Rebecca Clarke Viola Sonata. This staple of the viola canon was turning 100 years old in 2019. Inspired by the Coolidge competition’s history and influence on viola repertoire (this was the competition for which Clarke wrote her Viola Sonata), I set about trying to emulate a similar impact on viola repertoire. I announced a call for scores for solo viola by American women and received a generous contribution from the Nora Redman Fund of Louisville, Kentucky to support the project. But that was just the start. I expanded the project into a multi-year commissioning celebration of the 100-year anniversary of American women’s voting rights. Through winning the Faculty Research Grant from the Willson Center for the Humanities and Arts at the University of Georgia, and another generous contribution from the Nora Redman Fund, I was able to budget two calls for scores by American women composers in both 2019 and 2020, and two commissions by Gabriela Lena Frank and Gity Razaz. The project was titled VIOLA2020 after the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment.

But alas, we all know what happened in 2020! What follows in this article is the story of my entire experience with these projects—from ideas to reality, recordings to publications, with setbacks and side roads, and an intervening global pandemic. This has provided me with an invaluable perspective on how to take part in cultivating, advocating, and teaching important works of art that address some of the imbalances in our profession. And I hope that by sharing the insights I have learned, other performers and teachers will find a roadmap for embarking on a similar journey.

My History of Creating New Music

I have had the new music bug for quite a while. During my undergraduate degree, I took composition lessons and was heavily involved in the Imagine New Music Festival at the University of Memphis where I grew up and went to college. Later, I completed my graduate work at Peabody Conservatory at Johns Hopkins with the commitment to commission works by my classmate composers. However, it took me until 2009 and my Carnegie Hall debut recital with my sister duo Allemagnetti to finally dig my teeth into my first big commissioning project. Featured on that Weill Hall debut recital were three new commissions by Kamran Ince, Thomas Pasatieri, and Garrett Byrnes. We also performed a work by Kenji Bunch and all four composers were in attendance. My commitment to changing the canon and to broadening the repertoire was cemented. Arriving at the University of Georgia in 2010 helped foster my development of recordings thanks to the on-campus support of creative research. I completed my first album in 2012 (Allemagnetti) and got started on my next right away, including another commissioned work by Garrett Byrnes and three other excellent works by modern American composers Christopher Theofanidis, Stephen Paulus, and Kenji Bunch (Modern American Viola Music).

But it was glaringly obvious that my own gender was missing from my creative research. I responded to my own criticism by raising the money to make another album, and commissioned Libby Larsen to write the cornerstone of the recording: a solo viola piece called Stunned (from the album Viola Alone: Old, New, and Borrowed). It was through working with her, and the satisfaction I found in championing works by women that I have since focused my creative research on promoting women composers. Best practices start from within.

Presently, I’m devoted to uncovering new music and old music by women composers, and to continued commissioning of new works by women. I’ve been lucky to find an ally in the Nora Redman Fund that supports my commissioning and recording habit, as well as continued support from the Willson Center at UGA. There is so much unknown great music out there that was historically erased due to gender issues, and still even more great music to be written, recorded, and shared.

Collaborating with Composers and Pandemic Pursuance

Finding an exceptional composer is very much part of a successful commissioning project because the last thing that one looks for is a piece that goes back on the shelf immediately after its premiere. One thing I’m extremely proud of with the Womens Writes project, like my earlier projects, is that not one piece on that album is something I wouldn’t want to play again and again.

When deciding whom to commission for the VIOLA2020 project, I dove deeply into the repertoire of the women I was considering, as I wanted to be sure that I loved their music. Gabriela Lena Frank is a household name in new music circles. She is an inspiring advocate for new music and marginalized composers through her Creative Academy of Music. Gity Razaz was not a composer I was familiar with, but I was immediately drawn to her distinct voice in music, her grand and often bright sound, which is so clearly and fluently influenced by her Iranian-American heritage. Both composers agreed to write for me for the centennial celebration and the premiere dates were set for April 2020 for the Frank and November 2020 for the Razaz. The scores arrived, and a major concert event was planned for April 2020 to celebrate the Nineteenth Amendment Centennial—ensembles and faculty from the entire school of music were confirmed, all performing works by women, both large-scale and small, and the Ethyl Smyth Suffragette song “Shout, Shout” was to be sung in the aisles of the concert hall to open the concert. Yet with the arrival of the scores also came the arrival of the global pandemic, and all these plans seemed they were for naught.

Like many others in the music world, I reimagined and rebranded with new COVID-era methods to get these remarkable new works out to the public. I had already performed the 2019 call for scores winner (Virginia Samuel’s lost angel) in March 2019 and had premiered the 2020 winner just the week before lockdown (the hauntingly beautiful for Hypatia *by Kirsten Volness). I ended up using a new medium in premiering the Razaz work Spellbound: since I couldn’t have a live audience, I recorded a concert film and included interviews with the composers and performers between each work. Gity Razaz gave a small introductory video, as did the Athens amateur composer and violist Barbara Redman whose work Elegy *is also included on my album. While the commission wasn’t premiered before a live audience, I was very proud of our work under the circumstances. Unlike the Razaz, however, it took a while longer to realize the premiere of the Frank.

Given that neither composer was local to me and 2020 was not a great year for traveling, both pieces had to be workshopped via the newfound online experience of Zoom. I performed each work for the composer and got their feedback online, and both experiences were life-altering. Working with Frank on her piece was like a masterclass in humanity. I left our session feeling empowered as a human, as a woman, and validated as an interpreter and musician. Working with Razaz taught me so much about making new sounds with my viola in order to get across the gestures reminiscent of her childhood: Persian instruments like the kamancheh and the erhu were things that I’d never tried to make my viola sound like before, and I have since taken those abilities with me. Working with composers on their pieces gives such insights. I remember Libby Larsen describing the inspiration for the piece she wrote for me, Stunned, as the moment you get the most terrible news—that instance of shock when you’re almost blinded by the words or sights you’re hearing or seeing. And Frank likened the whirling section of her work for me Soliloquio Serrano No. 2 as the dizzyingly high-altitude windy lack of oxygen felt upon achieving a high mountain peak. She described another low moment of the piece as the silt exploding around a dropped anchor while resonating in deep viola sound. Zoom meetings can make the world feel more closely connected and I’m very thankful to the composers for their time, their music, and their inspiration.

Eventually, I was able to premiere the Frank piece in March 2021 in a joint recital with a colleague celebrating women’s history month. It was a smaller celebration than the initial school-wide project, but at last, a successful premiere. Getting my producers, Tim Redpath and Rachel Calaminus of Horizon Music Productions from England to the US for the recording sessions would prove unachievable for another year due to the UK pandemic travel restrictions. We finally scheduled the recording for May 2022, and recorded the album for three days in the Hugh Hodgson Concert Hall at the University of Georgia Performing Arts Center. We spent the summer perfecting the album and released it to Arabesque Records for promotion, which occurred in early 2023. The cover art, by Judith Heald titled Shout, Shout (after Ethyl Smyth’s song) was inspired by the Frank work. In all, the recording was only two years late, and I rebranded it as Womens Writes, since VIOLA2020 had bad connotations by this point. Better later than never for such a wonderful project!

All the works thematically tie together, as each composer happened to use similar techniques including bariolage, arpeggiating across the strings, and whirling gestures. Choosing the order of the pieces evolved quite easily. I chose the Frank piece to present the record as a soliloquy of strength. The piece for Hypatia was a lovely transition from the prayerful ending of Frank’s piece into the mournful contemplation of the open perfect intervals of Volness’s piece based on the story of Hypatia of Alexandria and her violent death. Spellbound seemed a natural next work; following the desperate but hopeful ending of for Hypatia, the ears would naturally be attuned to the new sounds presented in Spellbound. The resonant C string of Redman’s Elegy seemed an organic way to bring the album back to reality through the elegiac resonance of mourning for a miscarriage. Redman says the end of this work is a “yelling at God” moment which transitioned easily to the arguments that Virginia Samuel brought in lost angel. This 2019 piece was written and inspired by the combative nature of the two sides of Brexit (as Samuel is an American composer living in the UK), and the opposing voices are evident in the writing.

The first five works on the album were written for or commissioned by me. The next four works I chose very carefully to fit both my purpose and the tone of the recording: evocative, soulful works for viola alone by American women composers. Ko’u inoa by Leilehua Lanzilotti was introduced to me by one of my graduate students and was a perfect fit with what the composer calls its homesick bariolage. I jumped at the opportunity to learn Jessie Montgomery’s Violin Rhapsody when she released her transcriptions in early 2021. I was thrilled to find the Kouyoumdjian work for solo viola filmed by Hilary Herndon during the lockdown period of 2020, as I had performed her Boy and a Makeshift Toy in 2021 on the same recital as the Gabriela Lena Frank premiere, and loved her compositional voice. Lastly, I closed the record with the work by Reena Esmail that I absolutely fell in love with: Varsha (Rain), which is a compelling work with escalating gestures inspired by her Indian-American heritage.

Performance and Pedagogy

Working through these composers and vetting both the works and the calls for scores provided numerous pedagogical results. I was able to pass along some of the works to my college students and some of these were premiered by my studio. I’ve changed my own best practices when crafting concert programs for both myself and my students. I know that putting one piece by a woman composer on every program can be considered tokenism. However, putting at least one woman composer on every single program is a consistent and fundamental change. This is what I aspire to do, but is also something I have instilled in my students. They know that rarely will they be encouraged to program a Bach and Brahms recital without finding something of substance from the American Viola Society’s Underrepresented Composer Database.1 Having familiarized myself with the catalogs of so many living women composers, I can now also call on that familiarity in chamber music.

This project has also crystallized my work with my studio to do a yearly project based on uncovering works by marginalized composers. Started as a lockdown jury project, each student in the studio researched the American Viola Society’s UC Database and found a piece to perform digitally, along with a small explanatory video. We presented a similar project again in a live recital in February 2023 at the UGA Performing Arts Center. In 2024, we are performing a BIPOC feature recital celebrating Black History Month. All of these projects celebrating and uncovering marginalized composers stem from my personal research and my work with fixing, in my way, what I see as a broken representation on our stages of the works of so many of our population. Today’s students understand this and take these best practices with them, to their audiences, their future students, and their future colleagues.

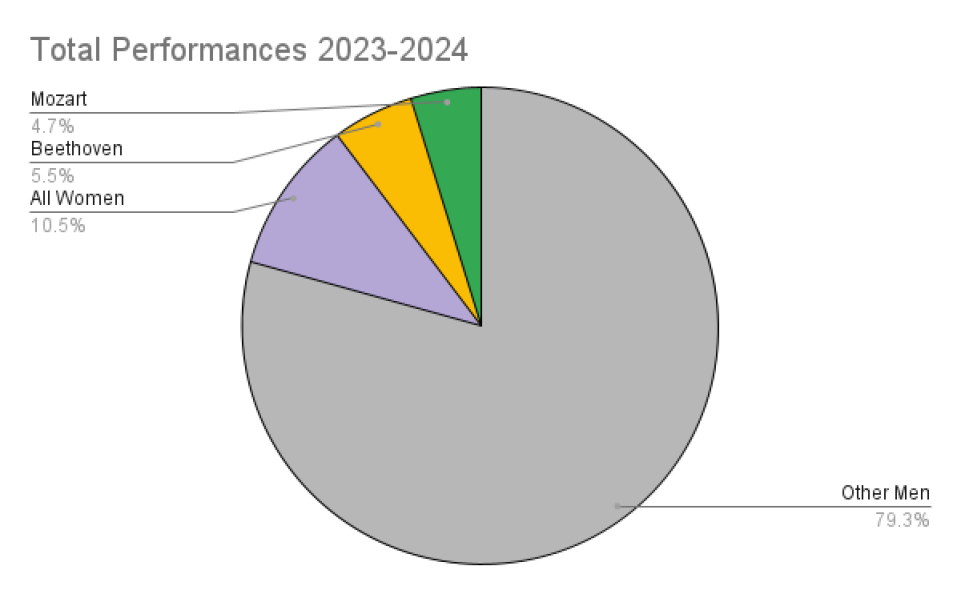

Sarah Baer, in her statistical study of the representation of composers on the subscription concert programs of the major symphonies of the US, found that 89.5% of works being performed in 2023–2024 were by men. This data shows a major backsliding of orchestras’ programming improvements from previous seasons following the influences of #metoo and #blacklivesmatter. Baer writes: “Combined performances of works by just two composers (Beethoven at 74 performances and Mozart at 63) equal just three fewer performances than all of the works by women combined.”2

Figure 2. Composers performed by symphony orchestras in the United States in the 2023–2024 season. Image courtesy of Women’s Philharmonic Advocacy, wophil.org.

These statistics are not new news, nor surprising: we all see the concerts and the repertoire being performed, and we all (or most of us) love our Mozart and our Beethoven. It is within our circle of control to do differently, and better, each as individuals in our own spheres, with our students, and with our listeners. This project, and my next one which is already underway, are small by comparison to that which a major symphony orchestra might do, but I am proud that my contribution has changed the available repertoire for the viola by women composers. My next project, titled Women’s Works, past present and future, focuses on past works that suffered gender-based historic erasure (Ruth Gipps, Kalitha Dorothy Fox, Dorothy Howells), present works (a commission by Mary Kouyoumdjian for viola and piano), and the work of the future of women in composition from virtuoso violinist Tessa Lark, along with another international call for scores for viola alone or viola and keyboard instrument by woman-identifying composers. The premieres of this project are scheduled for March 2024 (women’s history month) and the recording is scheduled for May 2024 at the University of Georgia.

Inspiring Young Musicians

Choosing inclusionary repertoire has impressionable effects on developing musicians of all ages and levels. Incorporating inclusionary repertoire develops self-confidence for students especially when their demographic is represented. My early musical experiences greatly influenced my feelings of belonging, my feminine strength in a considerably male-dominated field at the time, and my own need to advocate for my gender (and also for groups that are marginalized in classical music). I was raised in a musical and academia-based family as a Suzuki child, participating in a learn-to-stand/learn-to-hold the violin program when I was a baby in the 1970s. I studied Suzuki piano with Linda Jackson (founder of the Suzuki Program at the then Memphis State University, now University of Memphis) at age three, and started Suzuki violin with Ray Pak-Chung Cheng, who was a student of John Russell, when I was three-and-a-half years old. I still use some of their stories in my teaching to this day.

I was greatly influenced by the programs but was shocked and emboldened by my first interaction with music by a living composer. When I was around age eleven, I participated in a national composer/performer collaboration organized by a local Memphis all-rounder, John Boatner. This exchange paired young, advanced musicians with young, advanced composers across the US. I was matched with a young girl who wrote a piano sonata in three movements. I was struck by the fact that this young lady was composing—I had already played so much Brahms, Beethoven, Mozart, and Bartók and thought that quality composers had to be male and dead! Her piece was bright, fun, well-crafted, and playable. Furthermore, it was written by a little girl who was just my age! This had a huge effect on me. All at once the doors were wide open for me to play music by women, search out music by women, and look for more women mentors in music. All of this helped me realize that I could pursue any field in music, or life for that matter.

This experience meant that when I next encountered a woman excelling in a man’s field, I was inspired and armed for the discussion about her role in this difficult position. I was very lucky to be taught by Carol Crawford, the assistant conductor of the Memphis Symphony and the conductor of the Memphis Youth Symphony in the early 1990s. I interviewed her for a high school project and learned so much about being a woman in a man’s profession. She was artistic, powerful, and succeeding in her field, and her influence considerably contributed to the strong backbone I needed to be competitive in my profession.

Having had years of experience with the Suzuki Method, I continue to use it in my own early-level private studio teaching and remain lovingly familiar with the repertoire. I am somewhat abreast of the supplemental materials and am grateful for the addition of the sight-reading and repertoire books that were missing when I was very young. I was struck by my son’s excitement and immediate interest in the fact that his violin teacher added the required scores of Music by Black Composers compiled by Rachel Barton Pine and the Black Composer Project.3 Many young people today are far more aware of the need for diversification than previous generations were.

If I somehow had my youth to do differently, I would have liked to have been introduced earlier and more thoroughly to music by women. I always keep in the forefront of my mind that it’s not my job to tell students what they cannot do—they are resilient and will try anything, sometimes with great success, until they are told otherwise. On the flip side, they won’t know what they can do unless a seed is planted in their psyche. A few next steps, or seeds that we could use to help in the future, are:

- Infusing the repertoire instead of having music by women (and BIPOC) composers be supplemental

- Ensure quality of repertoire so as not to promote tokenism or promotion of less quality music for show

- Add a large quantity of works so it is a fully integrated best practice

- Seek out works by living composers for inclusion and promote the creation of new work

- Keep our teaching methods as living entities, evolving as the needs of our future students change

In thinking about the available repertoire for young upper-string players, I did a shallow dive and found Violin Music by Women volumes 1–4, compiled and edited by Cora Cooper, which is available also for viola. Cora says on her website that Violin Music by Women “provides short fun pedagogically sound pieces” and provides an embedded link for hints on where to include these pieces in the Suzuki progression in Books One and Two.4 The idea of this kind of supplement is invaluable. Another wonderful resource of which I am a huge fan is the website and organization Boulanger Initiative, which advocates for women in music.5 It is notable that the co-founder of this initiative, Dr. Laura Colgate, is also a graduate of my same all-girls high school in Memphis. If there is other material out there that I am unaware of, I would be thrilled to be told and would immediately investigate using it.

I provide these personal anecdotes because it’s important to give some insight into what I’ve learned from my projects, and how I might have changed things for myself in my fundamental and pre-collegiate years. My Suzuki background didn’t expose me to new music or any music by women composers in violin or piano. Those first two experiences I shared above were my lightbulb moments. I would love to see the young musicians of the future not have to consider such things.

I keep celebrating women composers and hope you will all join me in continuing to change the canon and bridge the gender gap on our stages and podiums, concerts and streaming platforms, and in our classrooms, studios, and printed material.

Notes

1 Website: https://www.americanviolasociety.org/composer-database/

2 Sarah Baer, “2023–2024 Season: By The Numbers,” Women’s Philharmonic Advocacy, June 2023, accessed last January 8, 2023, http://www.wophil.org/2023-2024-season-by-the-numbers/

3 Website: https://www.musicbyblackcomposers.org/

4 Website: https://www.violinmusicbywomen.com/

5 Website: https://www.boulangerinitiative.org/

Violist Maggie Snyder is Professor of Viola at the University of Georgia, Principal Violist of the Chamber Orchestra of New York, and is on the Artist-Faculty of the Brevard Music Festival. She has performed solo recitals, chamber music, concertos and as an orchestral musician throughout the United States and abroad in such halls as the Kennedy and Kauffman Centers, Carnegie Hall, and the Seoul Arts Center, and in the UK, Greece, Korea, and Russia. She was a semi-finalist of the 2001 Primrose International Viola Competition, and made her recital debut in Weill Recital Hall at Carnegie Hall with her sister duo, Allemagnetti in 2009. She has released four solo recordings since 2012 on the Arabesque Label and one collaborative recording on Parma. Maggie is a proud Suzuki baby having been a 1970s student of the Suzuki Piano School established by her teacher Linda Jackson at the University of Memphis and also studied with Pak-Chung Cheng, violin, who was a student of John Russell. Her daughter is at the end of Book Two Suzuki Cello and her son plays on her Cremona-made 1984 Lynn Hungerford three-quarter-sized violin from her Suzuki days.