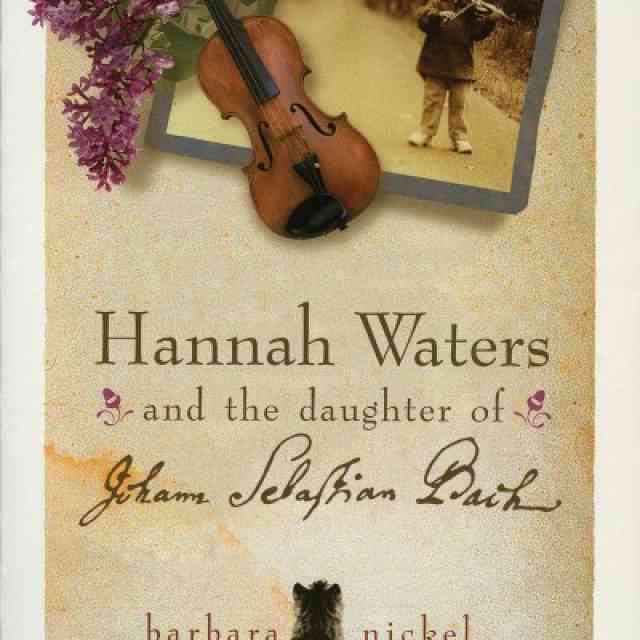

Figure 1. Front cover of Anna Magdalena Bach’s Notebook of 1725. D-B Mus. ms. Bach P 225. All images are courtesy of Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Musikabteilung mit Mendelssohn-Archiv.

Near the end of Volume One of the Suzuki Violin School, students encounter a series of three Minuets, “Minuet No. 1,” “Minuet No. 2,” and “Minuet No. 3” in Suzuki parlance, long attributed to Johann Sebastian Bach.1 Of the three Minuets, only the first—and the least widely known outside of the Suzuki world—was actually composed by Bach. Minuet 1 comes from a very early keyboard suite, Ouverture in G Minor, BWV 822, composed when Bach was at most twenty-two years old, perhaps even a few years younger. While the composer of Minuet 2 remains anonymous, Christian Petzold (1677–1733) was identified in the 1970s as the composer of Minuet 3.2 We may lament the dismissal of Bach’s authorship for this beloved dance, one of the most widely recognized pieces in all of Western classical music, but Bach’s loss is our gain. The story of how this simple tune made its way from a forgotten musician’s quill into the repertoires of countless young musicians three centuries later speaks directly to the heart of the Suzuki Method.

![Figure 2. J. S. Bach, Partita no. 3 in A Minor (BWV 827). D-B Mus. ms. Bach P 225 [p. 1].](https://suzukiassociation.org/images/med/news/Lowe_Fibure_2_AMB_1725_p1.1690335529.jpeg.converted.jpg)

Figure 2. J. S. Bach, Partita no. 3 in A Minor (BWV 827). D-B Mus. ms. Bach P 225 [p. 1].

The source that bequeathed Minuet 3 to us is not the original manuscript of Petzold’s suite, housed in the Saxon State Library in Dresden, but rather a mother’s personal musical book of astonishing intimacy, now in the collection of the Berlin State Library: Anna Magdalena Bach’s second Notebook. Perhaps a Christmas or anniversary present from her husband, a gift to celebrate the birth of a child (Wollny 2010), or maybe she chose it for herself (Yearsley 2019), this beautiful book was likely made by a bookbinder in Leipzig, the city where Johann Sebastian Bach worked and resided with his family for nearly three decades. It is bound in an elegantly decorated green cover, embossed with the initials “AMB” and the year “1725,” and fastened with a gold ribbon (Figure 1). When he inherited the Notebook, her stepson Carl Philipp Emanuel added the letters of her name after the embossed initials. Inside the cover, the Notebook’s 126 gilt-edged pages offer a remarkable glimpse into the domestic music making of the Bach family home.

![Figure 3. C. P. E. Bach, attr., Polonaise in G Minor (BWV Anh. 123). D-B Mus. ms. Bach P 225 [pp. 62-63]. Courtesy of Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Pre](https://suzukiassociation.org/images/med/news/lowe_figure_3all.jpeg.converted.jpg)

Figure 3. C. P. E. Bach, attr., Polonaise in G Minor (BWV Anh. 123). D-B Mus. ms. Bach P 225 [pp. 62-63].

The volume opens with two of Bach’s Partitas from the Clavier Übung, No. 3 in A minor and No. 6 in E minor, selected and copied into the Notebook by Johann Sebastian himself (Figure 2). Several short pieces follow—minuets, polonaises, marches, songs, and chorales—the majority of which were chosen and copied by Anna Magdalena. A handful of pages contain music composed and copied by the Bach children (Figures 3 and 4), and the Notebook ends with four pages detailing rules for figured bass, the first page in the handwriting of a young Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach and the last three written by Anna Magdalena (Figure 5). Minuet 3, in Anna Magdalena’s hand, is on page 44, the second piece she copied into her new musical Notebook (Figure 6). How did she come to know this piece? And what led her to copy it here?

![Figure 4. J. C. Bach?, [March] in F Major (BWV Anh. 131). D-B Mus. ms. Bach P 225 [p. 101].](https://suzukiassociation.org/images/med/news/Lowe_Figure_4_AMB_1725_p101.jpeg.converted.jpg)

Figure 4. J. C. Bach?, [March] in F Major (BWV Anh. 131). D-B Mus. ms. Bach P 225 [p. 101].

In the fall of 1725, the same year embossed on the cover Anna Magdalena’s Notebook, Johann Sebastian played two consecutive recitals on the new Silbermann organ in St. Sophia’s Church in Dresden, the Saxon capital where Christian Petzold was court organist and chamber composer (Wolff, 2013). It is presumedly on this trip that Bach came to know Petzold’s music, and he likely took back to Leipzig copies of his colleague’s simple, binary-form dances to use in his own teaching. But Johann Sebastian was not the only parent-teacher of music in the Bach family home.

![Figure 5. Rules for Figured Bass I and II. D-B Mus. ms. Bach P 225 [p. 123-24].](https://suzukiassociation.org/images/med/news/figure5.jpeg.converted.jpg)

Figure 5. Rules for Figured Bass I and II. D-B Mus. ms. Bach P 225 [p. 123-24].

![Figure 6. The so-called “Minuet 3.” Christian Petzold, Minuet in G Major from Suite de clavecin, c. 1725. D-B Mus. ms. Bach P 225 [p. 44]. Courtesy of](https://suzukiassociation.org/images/lg/news/Lowe_Figure_6_AMB_1725_p44.jpeg.converted.jpg)

Figure 6. The so-called “Minuet 3.” Christian Petzold, Minuet in G Major from Suite de clavecin, c. 1725. D-B Mus. ms. Bach P 225 [p. 44].

Though remembered today mostly as Bach’s second wife, the mother of thirteen of his twenty children, and stepmother to the four surviving children from his marriage to Maria Barbara Bach (1684–1720), Anna Magdalena was herself a talented professional musician from a musical family. Indeed, she held the top rank and highest pay as a princely court singer in Cöthen. It was there that she met her future husband, who was at the time Capellmeister of the Cöthen Court Capella. She continued in her professional position in the Capella until the Bach family moved to Leipzig, where her musical activities became mostly domestic in nature—which is not in the slightest to diminish or devalue them. Not only did Anna Magdalena continue to perform professionally, returning to Cöthen for occasional special performances, she became a highly regarded copyist for Johann Sebastian’s music. Entrusted with some of his most difficult and complex compositions, her musical handwriting simulated her husband’s so well that their calligraphy is often difficult to tell apart. Along with her splendid copies of the cello suites, the sonatas and partitas for violin, the six organ sonatas, and sections of both books of The Well-Tempered Clavier, she produced parts for the St. Matthew Passion and for many of the weekly cantata performances in Leipzig’s churches, sometimes quite urgently. She was also the first music teacher of several of Bach’s children.

It is likely in this vital role that Anna Magdalena selected the many minuets, marches, and polonaises for inclusion in her 1725 Notebook, almost all of which were composed by musicians other than her husband. These galant pieces vary in both level of difficulty and compositional style. Living alongside a Rondeau by François Couperin (Les bergeries, from 6th Ordre, published in 1717) and a Polonaise by celebrated opera composer Johann Adolf Hasse are several marches and polonaises attributed to Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (Figure 3) and a single march possibly composed by a very young, perhaps ten years old, Johann Christian Bach (Figure 4). These pieces are youthful compositions by two of Bach’s sons, one Maria Barbara’s child and the other Anna Magdalena’s, both of whom would later be recognized during their lifetimes as two of Europe’s most important musicians and composers: C. P. E. Bach (1714–1788) was a member of the Royal Orchestra in the service of Frederick the Great and later succeeded Telemann as Capellmeister in Hamburg; and J. C. Bach (1735–1782), the so-called “London Bach,” became music master to Queen Charlotte of Great Britain after several successful performances of his operas at the King’s Theater in London’s West End. The contents of Anna Magdalena’s Notebook—an assortment of short galant dances by a variety of composers, along with the songs, chorales, aria fragments, suites, and a prelude, most of which are by Johann Sebastian—thus formed an ideal collection of music for instructing her children in singing, dancing, keyboard playing, and composition—and, of course, for Anna Magdalena to play and sing herself for her own musical pleasures.

Three hundred years after Anna Magdalena Bach began assembling her 1725 Notebook of music, Minuet 3 still lives alongside tuneful songs, short dances, and technical exercises in the Suzuki repertoire. Its illustrious pedagogical legacy continues just as it began: a small, unassuming piece purposefully selected by a loving and devoted teacher to nourish the world’s youngest musicians. When we as teachers and parents play, sing, listen and perhaps even dance to these timeless minuets with our students, our studios, and our children, we follow in the footsteps of music history’s most beloved musical mother.

Notes

1 These three minuets also appear in the Viola, Cello, Flute, and Piano repertoires; the Bass, Harp, and Recorder repertories contain two of the three.

2 Christian Petzold is also the composer of the Minuet in G Minor in the Suzuki Recorder School and Suzuki Piano School repertoires.

References

Dadelsen, Georg von, ed. Klavierbüchlein für Anna Magdalena Bach (1725). In Urtext der Neue Bach-Ausgabe. Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1985.

Wolff, Christoph. 2013. Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician. New York: W. W. Norton & Co.

Wollny, Peter. 2010. “‘Ein grüner Quartband: 67 Blatt’: Das Notenbüchlein der Anna Magdalena Bach.” In Vergnügte Pleißenstadt: Bach in Leipzig, ed. Anselm Hartinger. Berlin: Lehmanns Media.

Yearsley, David. 2019. Sex, Death, and Minuets: Anna Magdalena Bach and her Musical Notebooks. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Melanie Lowe

Melanie Lowe is Associate Professor of Musicology at Vanderbilt University’s Blair School of Music. Her research focuses on constructions of musical meaning, from topic theory in late 18th-century music to uses of classical music in 21st-century media. Her book Pleasure and Meaning in the Classical Symphony (Indiana University Press, 2007) explores why the public instrumental music of late-eighteenth-century Europe has remained accessible, entertaining, and distinctly pleasurable to a wide variety of listeners for over 200 years. Her co-edited volume Rethinking Difference in Music Scholarship (Cambridge University Press, 2015) situates difference within broader debates over recognition and freedom to reveal why differences and similarities among people matter for music and musical thought. Among her other musicological publications are articles and reviews in The Oxford Handbook of Topic Theory, the Journal of Musicology, American Music, Beethoven Forum, The Cambridge Companion to Haydn, and the Journal of the American Musicological Society. Lowe is also deeply committed to the scholarship of teaching, and her publications on pedagogy include articles in the Journal of Music History Pedagogy, the Norton Guide to Teaching Music History, and the edited volume Teaching Music History. She has presented scholarly papers throughout North America, Europe, and Australia, and among her numerous awards are the Madison Sarratt Prize for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching, the Reverend James Lawson Lectureship for Service and Leadership, the Blair Faculty Excellence Award, and the Princeton Graduate Alumnae Excellence in Teaching Award. Lowe earned her Ph.D. and M.F.A. in Musicology from Princeton University and her B.A. from Smith College