Clifford Cook Memorial Scholarship

The Clifford Cook Memorial Scholarship is awarded annually to a string player for Suzuki teacher training.

Biography

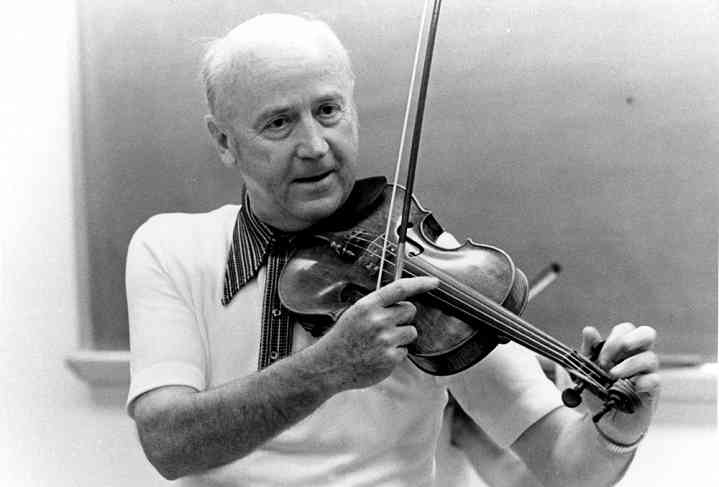

Clifford Cook first learned of Shinichi Suzuki’s remarkable work in Japan in the fall of 1957. A Japanese student in the Oberlin College School of Theology, Kenji Mochizuki, brought a film of a national concert by Suzuki children in Tokyo to Cook, a Professor of Strings in the Oberlin College Conservatory. Much impressed by the performance of the children, Cook began corresponding with Dr. Suzuki and Dr. Honda to learn more about the background of their amazing performance. The film was shown to Oberlin classes and to the Ohio String Teachers Association meeting in Oberlin that May. Among the few teachers who saw the film were John Kendall and Robert Klotman, both to become prominent exponents of Suzuki and leaders in string education.

Cook’s sabbatical in 1962-63, spent observing string teaching throughout the US, Europe, and Japan, convinced him that Suzuki’s Talent Education system was by far the most promising development in the world of string education of that time. A violin program for young children was started in Oberlin in the fall of 1963 which included teaching by Japanese graduates from Dr. Suzuki’s school. Hiroko Yamada, Hiroko Toba, Yuko Honda, Eiko Suzuki, and Kazuko Numanami all taught at Oberlin through the years.

The 1964 tour arranged by Kendall, Klotman, and Cook garnered much attention and put the movement firmly in gear in this country. Dr. Suzuki conducted workshops in Oberlin and many other locations during subsequent summers, and the annual October tours by Japanese teachers and children aroused much interest.

While teaching Oberlin children, Cook also did workshops and gave concerts in many places throughout the US. In 1969 he returned to Japan for further study. In retirement he wrote a book, Suzuki Education in Action, published by Exposition Press in 1970. Cook also wrote numerous articles as well as another book, Essays of a String Teacher, which was published in 1973 and includes extensive sections on Suzuki. A series of his articles was also translated into Japanese and published by the Talent Education magazine in Japan.

Remembering Clifford Cook

By Art Montzka, 1997

Marilyn and I have particularly fond memories of Clifford Cook. Through our years at Oberlin we had our lockers near his teaching room in Rice Hall. I really enjoyed his string classes and learned much in them. His dry wit and quiet but determined manner kept things moving in a very interesting and entertaining way. We often would stop in to talk to him after class or at the end of the day. His humor also comes out in his books—we jokingly renamed his book that we used as a reference, “String Teaching and Duck Shooting!” He would say, “Shoot pigeons and not ducks when you play the violin,” instead of merely saying hold the scroll up when you play.

I graduated from Oberlin the year before Clifford obtained the famous film showing Japanese Suzuki students playing the Bach Double Concerto, the moment that has had such far-reaching impact on all of us in the Suzuki movement. And after that moment he was a true pioneer in experimenting with Suzuki teaching himself, in spreading the word about it, and in bringing Japanese Suzuki teachers to this country. He certainly deserves a great deal of credit. He was a wonderful founding father of the Suzuki movement in this country.

Well done Clifford. You have aimed high—at the pigeons, and not the ducks!

World’s Best-Known Folksong

By Clifford Cook

Wolfgang Mozart composed in 1778 a set of 12 Variations on “Ah, vous dirai-je, maman!” Written for the piano of that period, these variations are based on a French folksong whose words begin (in English translation), “Ah, I will tell you, mama!” English-speaking people call this song “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” with the next lines as follows:

“How I wonder what you are,

Up above the world so high,

Like a diamond in the sky.

Twinkle, twinkle, little star,

How I wonder what you are.”

This children’s song has long been a world favorite. Mozart’s variations on it are frequently played in recitals by concert pianists. Many other composers have written variations on the tune—for example, Dohnanyi’s “Variations on a Nursery Tune” for piano and orchestra.

W. A. Mozart, one of the best-known child prodigies in music, was a superb example of Talent Education. Born into a musical family, the baby was enveloped in music from birth. His father was a prominent violinist, teacher and author. Wolfgang’s exceptional ability as performer on both violin and piano, and his great promise as composer-improviser developed very early and were soon widely acclaimed throughout his extensive tours. His short life-span of 35 years has often been attributed to early exploitation, but Mozart achieved much more in his lifetime than did most people who lived two or three times as long!

In Salzburg, Austria, is the Mozart Geburtshaus and Museum. Among many interesting items there are Mozart’s tiny child’s violin and bow and his larger concert violin (a Jacob Stainer). Did young Mozart play the popular French folksong on his little violin? I believe he did.

Anyone who knows Shinichi Suzuki or has read his book, Nurtured by Love, is aware that Mozart is Suzuki’s favorite composer. Is it any wonder the first piece in the Suzuki Violin Method is Dr. Suzuki’s own “Variations on Twinkle?”Could his knowledge of Mozart’s remarkable early achievements on violin and piano, of how the baby was raised in a superior musical atmosphere from birth, etc., have inspired Suzuki, perhaps unconsciously, in conceiving his system of Talent Education? Possible, but only Dr. Suzuki can answer that question.

Many, many thousands of young children have learned to play the violin and some other instruments by starting with the Suzuki variations on this old French tune. How many millions of performances of it have been given? Astronomical! More than anyone else, Dr. Suzuki has made this tune the “World’s Best-Known Folksong.”