When I think of Rick Mooney, the descriptive words start flowing: friend, teacher, mentor, bon vivant, innovator, colleague, teacher trainer, contributor, nurturer, cellist, author, composer, arranger, editor, organizer, and magician. Rick got his education at the University of Southern California, studying Suzuki teaching methods with Phyllis Glass and cello with Eleanore Schoenfield. He traveled to Japan in the spring of 1976 to connect with Dr. Suzuki and the Japanese cello teachers. As a specialist in the Suzuki method of teaching, he has given workshops and been a guest teacher throughout the United States, Canada, Asia, England, Australia, and New Zealand. His service to the Suzuki Association of the Americas has included positions on the Board of Directors and the Cello Committee as well as writing/editing articles for the American Suzuki Journal as its Cello Editor and formatting the new International Edition of the early cello books for publication. Additionally, Rick was one of the founding members of a professional performance ensemble named Quatracelli! which specialized in new compositions and arrangements for cellos. Rick taught at the Pasadena Conservatory of Music from its inception, training teachers and young artists.

I first came in touch with Rick when he asked me to teach at his new National Cello Institute Summer Program. He and Randee, his ever-supportive and gracious wife, hosted me for several days each year in their home before the Institute started. Our friendship began with late-night talks about pedagogy, cello, Suzuki-style teaching, and the state of the still-new Suzuki Association—enhanced by gourmet cooking and perhaps a fine bottle of wine. Rick’s father had encouraged a practical career in computer science and business, while his mother, a musician, provided piano lessons at age five and cello lessons at age eight, which instilled his life-long passion for music. His early teachers, Victor Sazer and Eleanore Schoenfield, shaped his cello destiny. The combination of music, math, and business sense gave Rick a unique perspective and contribution to the profession. I marveled at Rick’s discipline in organizing his life to reserve morning hours for musical composition activities. I called on him to help the SAA return to a sound financial footing during a financial crisis, and his selfless expertise helped us create the highest bottom line ever achieved at that time in the organization.

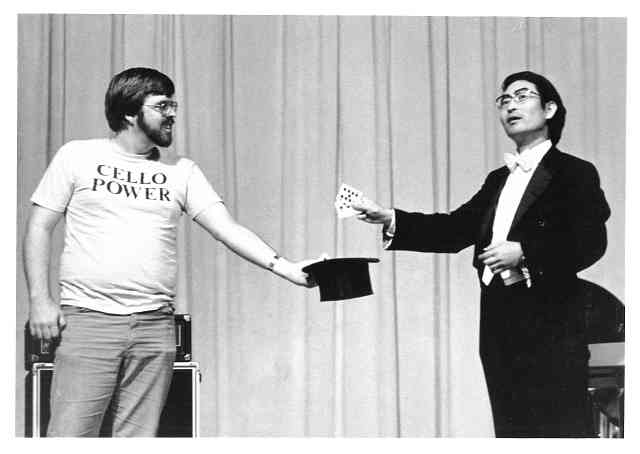

Rick Mooney (left) performing magic with fellow cellist and magic aficionado Toran Nagase at the American Suzuki Institute, Stevens Point. Photo by Art Montzka.

When Rick saw a need in the teaching sequence, he created supplementary material to enhance the process. This led to the creation of his nine books: two volumes of Position Pieces for Cello, two volumes of Thumb Position for Cello, Double Stops for Cello, as well as the Ensembles for Cello which enhance the first four Suzuki Cello books. Rick’s teaching materials are used worldwide, regardless of teaching approach, because they incorporate technical/musical skills development with the fun of ensemble playing. We can be grateful that we have an opportunity to hear Rick explain his teaching approach in an in-depth YouTube interview by Scarlett Arts entitled: Rick Mooney: A Guided Tour Through Position Pieces for Cello, Book One.

With the mindset that cellos needed the opportunity to meet and celebrate all things cello, Rick established the National Cello Institute (NCI) forty-eight years ago. He later created the NCI Winter Workshop to give cellists an opportunity to learn and play together during the year. Rick recognized that cello ensemble playing creates a strong bond and motivation among cellists. To this end, he wrote, commissioned, promoted, and published, through the National Cello Institute, ensemble music with varying levels of difficulty, so many ages and stages of cellists could enjoy making music together. Rick loved bringing cellists together and leading them in cello choirs, and he pursued this passion globally, earning him the moniker of Cellovangelist. In an interview titled “Cellovangelist,” done for the Music Institute of Chicago Cello Program, Rick shares his ideas:

But we wouldn’t do cello choir to the extent that we do if it were not for the fact that it is just so much fun. You have the fun of playing different repertoires, different harmonies and being in a big group with colleagues. I don’t think of the cello choir as a place for skill cultivation; that happens in the lessons. This is where they get to use all of those skills they have worked so hard to learn.

I select music for the choir that the students easily can play, which allows [me] to focus on refined musical nuances, not technique.

Performing in student groups can be powerfully motivating. I’ll remember forever the first time I played in a really good symphony orchestra, playing a really good piece—that sound, that feeling of excitement. So now, we get our five-year-olds in cello choir and give them a sense of playing in a big ensemble. And it’s fun. It’s just fun. When students hear peers playing at high levels and performing varied repertoire, eyes open, imaginations churn and standards rise.

Rick touched many lives. His influence radiates through his students, the teachers he trained, the colleagues he collaborated with, the families he guided, the programs he established, the audiences he reached, and the Suzuki world he served.

The Cello Committee in 1985 at Stevens Point ASI (Books Seven to Ten). Back Row, standing (left to right): Vaclav (Shuji) Adamira (TERI); Rick Mooney; Gilda Barston; Catherine Walker; Nell Novak; Carol Tarr; Marilyn Kesler; Anders Gron (ESA). Sitting: Toran Nagase (TERI); Tanya Carey. Committee member Carey Beth Hockett was absent from this photo. Photo by Art Montzka.