John & Catherine Kendall Memorial Scholarship

The John and Catherine Kendall Memorial Scholarship is awarded annually to a violin player for Suzuki teacher training.

Biography

John Kendall was born in 1917 in the town of Kearney, Nebraska, where his early years during the Depression shaped his entire life. His industrious father provided for his family by a great variety of means, such as cleaning and reselling used bricks and running a dairy and chicken farm. This rural, frugal and “Mark Twain-like” upbringing was never far from John’s daily living.

Music was introduced to John in the fourth grade, through his mother’s insistence that he play the violin. In 1939, at the age of sixteen and after eight years of study with a local violin teacher and a year of school at the local community college, John began his formal music training at Oberlin College. He thrived in the school’s musical environment, meeting influential performers and teachers, playing concertmaster and concerto soloist with the college orchestra and especially enjoying chamber music. He also met his future wife, Catherine Wolff, with whom he would share fifty-six years of marriage.

John was fortunate to find a teaching job soon after graduating, as violin instructor at Drury College, a small college in Missouri. After three years of teaching, and with the bombing of Pearl Harbor, John joined the Reconstruction and Relief Corps and later was inducted into the Civilian Public Service as a Conscientious Objector based on his Quaker heritage. He first worked in Tennessee as a forester and then on Welfare Island in the New York East River as a “guinea pig” in high altitude experiments. His move to New York allowed him to see his wife Kay, who was at home on Long Island during John’s service, and their newborn baby, Nancy. By the end of the war, while in New York, John completed a Master degree at Columbia Teachers College and studied at the Dalcroze School of Music.

In 1946 John and family moved to Muskingum College in New Concord, Ohio, where he served as orchestra director and violin instructor. Two year later he was appointed Chairman of the Arts Division. By now the Kendall family included three children, with Stephen and Christopher joining Nancy. The family moved temporarily to Bloomington in the mid-1950s for John’s doctoral work at Indiana University, studying violin with Tossy Spivakovsky and, during summers, Ivan Galamian.

It was the autumn of 1958, when attending the American String Teachers Association conference in Oberlin College, that John saw a revelatory film showing hundreds of young Japanese children playing at an amazingly high level. It inspired John, supported by foundation grants, to travel to Japan and see Dr. Suzuki’s work, about which he wrote, “In 1959, I began the adventure that undoubtedly changed the course of my life…it proved impossible to have had an experience such as those three remarkable months in Japan without re-evaluating my values.” It was awe-inspiring to be the first American to visit Dr. Suzuki and to see “Talent Education” in practice.

After returning from Japan, John’s life was filled with presentations, teaching, magazine articles, and the publishing of materials from the Japanese Suzuki Books 1 and 2, which John called “The Listen and Play Method”, based on Shinichi Suzuki’s teachings. A return trip to Japan in 1962 with more depth of study led to John’s coordination of the first “Talent Education Tour” to the United States, consisting of ten children from Japan, ages five to thirteen, performing throughout the United States. With help from Dr. Honda in Japan and Robert Klotman and Clifford Cook, both American String Teachers Association members, the 1964 tour included nineteen remarkable performances in twenty-one days, astounded music educators across the country and rarely left a dry eye among audiences. In 1967, John co-directed an historic trip to Japan of fifty-five American teachers for a two-week visit to observe Japanese teachers in action.

In 1963, the Kendall family had moved to the new Edwardsville campus of Southern Illinois University, where John’s position gave him the latitude to promote Suzuki Education around the country as he established a string department and formed a string faculty quartet-in-residence, the Lincoln String Quartet, which performed together for the next twenty-five years.

Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville, SIUE, became a mecca for string education, especially Suzuki training for youngsters as well as string teachers. John’s love of teaching students of all ages, his boundless energy and tireless drive, were contagious. He led the development of an innovative graduate program merging pedagogy and performance, in which, as an integral part of their studies, each graduate student was assigned ten Suzuki students and a Saturday group class. The “String House”, an old farmhouse abandoned on the campus, was the home for the graduate assistant Suzuki teachers; between the years of 1965 and 1992, nearly 150 students from all over the world came to SIUE to study with John Kendall in this two-year, intensive graduate program.

Even as students came to SIUE from around the world, John continued to travel widely to teach students and teachers. The last published writing by John was a memoir of his life he called Recollections of a Peripatetic Pedagogue. The endpapers of the book show maps of his domestic and international teaching travels. A colleague aptly called this indefatigable educator the “Johnny Appleseed of the Suzuki Method,” acknowledging that his teaching and leadership in the Suzuki movement has helped to spread the principles of Suzuki Education all over the world. John was very involved in the formation of the Suzuki Association of the Americas and served as Board President from 1974-1976.

The Edwardsville home, fondly called Toadwood Scrubs, was an eleven-acre property on which the Kendalls built a house surrounded by pond, barn, wood-working shop, music studio and a chicken coop. Toadwood Scrubs was a center of activity for all the graduate students. There was a pottery shop and kiln for Kay, an avid potter and artist, who was also a published author and community activist and gave nature tours on the land for classrooms and scout troops. Together, John and Kay instigated the Watershed Nature Center, a wetlands preserve and education destination for the town of Edwardsville, and a lasting tribute to the civic values of both the Kendalls.

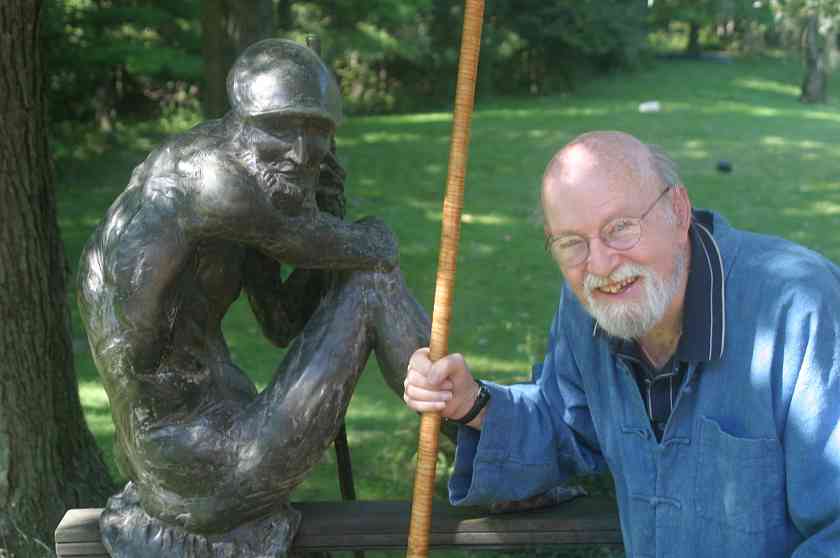

John lived in Michigan with his son Christopher and family during the last years of his life. For the Suzuki teachers of Michigan, it was wonderful having him so close. “Tuesdays with John” was the title for a once-a-month opportunity to witness John’s teaching of young musicians in a master class setting. Teachers from all around the state participated. His sparkle, wit, and wisdom remained extraordinary into his 93rd year. John Kendall was an inspiration to us all.

Quotes

John Kendall’s influence has been universal. He touched so many lives in such a positive way. My gratitude is unending for all that he gave me. I can truly say that I owe any success I have had in my career to him. He was my teacher, mentor and friend. Mr. Kendall, you are deeply missed by all who knew you.

—Beverly J. de la Bretonne

Some of the most profound things in our lives happen by chance. Growing up in Edwardsville studying in the Suzuki preparatory program was easily that for me. Just as we learn to appreciate the best things in hindsight, the influence of a brilliant teacher is often overlooked. A truly gifted teacher will make learning so effortless that we seem to have had the knowledge and the skill all along. Mr. Kendall’s humor, his passion, his intensity, his patience, his curiosity, his work ethic, his global views of music education, and indeed the world, inspire me daily. He is with me in every lesson I teach, every chamber music session I coach and every orchestra rehearsal I conduct. A few years ago I told him that I hear his voice as if he were sitting on my shoulder. He laughed and said my shoulder must be very sore! On one hand I miss his words of wisdom told with a story and a smile every day. On the other hand he is with me always as I hear his voice ask once again, Winifred, what is your rational for that?” I have been so incredibly fortunate indeed.

—Winifred Crock

I remember Mr. Kendall always teaching in jumpsuits. He had many ideas to approach common problems in different ways depending on the needs of the student. John Kendall brought Suzuki philosophy to life and inspired me.

—Jean Dexter

Mr. Kendall was famous for his teaching mottos, all of which continue to have a far-reaching impact on string pedagogy today. At Suzuki institutes, sounds of “Woody Waddy” and the “band-aid exercise” are heard from technique classes, while the words “we use the pieces to build our technique” are chanted from the group classes. He was fascinated by how the brain worked, challenging players to “stop-think-play” as they executed musical passages of any level of difficulty. He himself was constantly reading, thinking and pondering ideas for the betterment of string education. “Is this the only way? It is one way, but not the only way” was often mentioned at our lessons and pedagogy classes. I recall his sage advice to me as young, beginning teacher. After landing my first “real” job after SIUE, he reminded me to “Twinkle with honor.” Now many years later, that spirit remains, encouraging me with the start of each new student. Mr. Kendall’s legacy of inspiration continues on through the lives of countless teachers, students and parents all across the world.

—Christie Felsing, SIUE String House Graduate Assistant 1992-1994

The impact of John Kendall on my life has been profound and personal. He was more than my teacher, he was a wise friend and a sharing colleague who loved to call about a book he was reading, or an article he had read. Hardly a day goes by that I do not hear myself repeating his words, or incorporating his principles in my teaching. Each time that happens, I find myself still in touch with my teacher, my mentor, my friend.

—Susan Kempter

Although John Kendall traveled the world, he once told me he had never gone “on a vacation”. His work, family, friends, and students were all woven seamlessly into the fabric of his life and he enjoyed them all to the fullest. His passion for music and teaching were boundless and his ability to ignite that same passion in his students was legendary. Thanks to SIUE for the John Kendall Archives, where we can revisit photos of his historic trips to Japan, read his mischievous correspondence, and relish the history of a beloved teacher.

—Vera McCoy-Sulentic

It was Mr. Kendall’s pursuit in life to educate teachers and the world about the benefits of training in the Suzuki Method. He gave freely of his time and resources in training teachers and students here in the United States and across the globe. In order for the Suzuki Method of teaching to continue to grow in quality and quantity, he believed that the answer lies in finding ways to make training accessible and affordable to all teachers.

Mr. and Mrs. Kendall should be remembered as the “philanthropic duo.” They had love for humanity that included care for the environment, focus on quality of life, and a collaborative spirit that brought communities together. It was their dream to have a scholarship fund set up in their honor to help Suzuki teachers pursue training and to encourage experienced teachers to pursue “teacher trainer status.” As an SAA registered teacher trainer, my passion in life is to continue Mr. Kendall’s legacy, training teachers in the Suzuki Method, as they pursue teaching the students of the future.

—Kimberly Meier-Sims, Director Sato Center for Suzuki Studies, the Cleveland Institute of Music.

SIUE was an exciting place to be, with graduate assistants from all over the world, including the United States, as the Suzuki Method took hold and dramatically changed early string instruction in this country. John Kendall’s energy, charisma and sheer life force were absolutely breathtaking to me. He was able to communicate to his students that violin was fun and could be easy to play—with some smart practicing techniques.

—Carol Smith