Growing up in the rural Kithoka community in central Kenya, Bishop Lawi Imathiu didn’t have the opportunity to go to high school.

There were no secondary day schools in this rural area outside the town of Meru, just prohibitively costly boarding schools. He sought his own education and went on to attain several degrees, but back in Kithoka, educational opportunities were still thin on the ground. Until 2005, when, with help from the Ann Arbor, Michigan, organization that would become the nonprofit Kenyan Urithi Education Fund, the bishop founded the Bishop Lawi Imathiu Secondary School, followed by the Bishop Imathiu Primary School, steps in fulfilling the bishop’s vision of bringing education back home in Kenya.

Part of that vision of education includes music

The American teachers visiting the campus of Kenyan Methodist university

In January and February of 2011, seven string teachers from Michigan traveled to the Kithoka community to start a string program at the primary school. Four of the six teachers were Marilyn Kesler, Geri Arnold, Ann Schoelles, and Andrea Yun—all active members of the Suzuki Association of the Americas and Suzuki teachers. Also with the group were Larry Dittmar, KUEF Board President and retired orchestra director, and Bill Tennant, also a retired orchestra director, and Anne Ogren, a violin teacher.

In 2007, Dittmar, of Ann Arbor, traveled to Meru and Kithoka to set up the Meru Music Project. He eventually trained a former music project student named Boniface to teach the new band at BLISS. Dittmar has returned to Kenya several times to support the band, and now, start the string program at BIPS.

BIPS students gather outside for their morning devotions

The goal of the 2011 trip: to get a string program off the ground by teaching the students the basics of playing the violin, and to train Boniface in violin so he can carry on the program independently.

Once they arrived, the teachers’ first step was to size each student and organize the sixty eight violins, most of which were donated by Shar Music. As it turned out, 135, not 100, as the group expected, wanted to learn. The children were divided into four classes of twenty to fifty-five students each. The teachers saw a lot of great posture and bow holds—Yun believes they were so pliable in part because they had no preconceived notion of what a violinist should look like.

Students display their bow holds on the first day of lessons

Though it is not a Suzuki program, the teachers used a variety of tools familiar to Suzuki teachers: groups started with Twinkle rhythms (the teachers replaced the words “taka taka stop stop” with “wish I had a monkey” after learning that “taka” means “garbage” in the local dialect) and emphasized posture and proper bow holds. Because of these children’s specific situations, certain aspects of the Suzuki approach are impossible to meet: with very little access to audio equipment, the listening component is sporadic, when present at all. Furthermore, the primary school is a boarding school and many of the students are orphans, eliminating the possibility (often heart wrenchingly) for parental involvement.

Still, having teachers with Suzuki backgrounds was helpful. “We had strong teachers, with good Suzuki backgrounds, and the teamwork was terrific,” said Kesler. “We were able to accomplish a common goal.”

“Those kids wouldn’t have been all set up if it weren’t for a Suzuki background,” said Geri Arnold.

Some challenges the teachers faced included the language barrier—students at BIPS learn English, but naturally, some are more proficient than others. They also were tasked with not only teaching Boniface the violin, but how to teach it to the children. The physical conditions were not ideal—instead of classroom space, the groups met simultaneously in the school’s cafeteria, which was hot and noisy. A YouTube video posted by Yun shows a lesson in the cafeteria during a rainstorm, the noise from which was deafening. Regardless, the students were still motivated, engaged, and well-behaved, said the teachers.

Inspired by Suzuki

With so many committed Suzuki teachers present, the influence of the Suzuki philosophy was inevitable. “Just like with Suzuki, we’re not teaching violin because we want them to become concert musicians,” said Ann Schoelles. “It’s our means of connecting with these children. Our gift is being music teachers, and that’s how we can make the world a smaller place. We were learning about learning, that we can learn, and that we can learn together. We’re using the violin as a means to meet people, and to realize that everyone can learn.”

Though the teachers emphasize that it wasn’t a Suzuki program, at one point during a class, Geri Arnold turned to her fellow teachers and said, “This absolutely is Suzuki,” because the principle that every child can learn was so central to the work they were doing. “I felt like I was an ambassador for Dr. Suzuki,” said Arnold.

A fast-learning student on the second day of lessons

Why Africa?

Before and during her trips to Africa, Andrea Yun (who is spending July and August 2011 in Meru) has kept a detailed blog on her experiences. Early during her first trip, she questioned this type of service, wondering if her time and money would be better spent meeting more basic needs of Kenyan children, or volunteering in a program closer to home. Each teacher had a different way of thinking about these questions. For Andrea, the answer came after being in Kenya and speaking with others doing charitable work there. “Now that I’ve been there, I understand more fully—our dollars go very far in Africa,” she said. “There’s a side of me that feels very sad that we’re not doing this work in Detroit or in Saginaw… but the people in Kenya are on the trajectory of trying to catch up to the rest of the world in technology, political reform, education reform, things like that. They have a lot farther to go. As a result, I think our work there seems to have a bigger impact on the students and the community as well.”

Geri Arnold said that “any time with any children anywhere is worth your time and money. Yes, we should be doing this at home, too, but I think we are. Music is a giving career. Any opportunity you have to share is enough. It’s not just the fact that we’re teaching violin, we’re teaching so much more.”

The Students

A student displays his bow hold

If the teachers had any doubts about their work, working with the students quickly eased them. The students, ages nine to thirteen, were chosen because of their age so they may advance to eventually forming an orchestra at BLISS. Working with children from a vastly different background showcased many of Dr. Suzuki’s principles. “They felt so special for the attention,” said Yun. “What stuck out the most to me is that what we were giving them was a feeling that they’re unique in this world. What’s really great is helping them to feel not only that sense of accomplishment and that they’re special, but that there’s something bigger out there and that they can go get it if they want to.”

The children left an impression on the other teachers, as well. “When we asked the students, ‘Would you like to try this again?’ The answer was always, ‘yes!’” said Kesler. “Repetition was not a problem. They met the challenges we gave them with eagerness and with happy faces, and they took the responsibility of being the students chosen to do this. It was terrific… They’re unspoiled. They are willing to try and do their best. They’re not afraid. They have no stereotypes that say, ‘Oh, you can’t play the violin.’ They all think they can play the violin. If they’re so underprivileged, they’re also so unspoiled, and they’re happy.”

“They were poor in their facilities, but they were rich in their desire,” said Schoelles.

Outcomes and Future Hopes

By the end of their stay, the teachers accomplished much with the relatively few resources they had. “The children had the instrument in their hands and instruction with the instrument for a total of six hours,” said Kesler. “What we were able to accomplish in that time was unbelievable. The children had good violin posture, they had good bow holds, they were able to play with a straight bow, with a good detache bowing. The older children especially were able to play ascending and descending scales and Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star. Our goal was to give them a strong foundation—not to teach them so many tunes as to teach them good technique for the beginning. We were more successful in that than I think anybody would ever think possible, with the limited amount of time we had.”

The program ended with a concert for the community and schools. Yun wrote on her blog that the primary school violinists performed the E String Concerto, A String Concerto, I’m a Little Monkey (walking up the E string), and Chopsticks (triplets on the E string). The BLISS Band and Boniface performed, as well.

The violins were left to the school as a gift so the program will carry on after the American teachers left, with the hope that the program will eventually become self-sustaining. The teachers also left other materials, music, and CDs, which the principal has promised to play as often as possible. “It was such a successful start to this program,” said Yun. “Having so many experienced teachers there at the same time to jumpstart this program was a great way to get it going.”

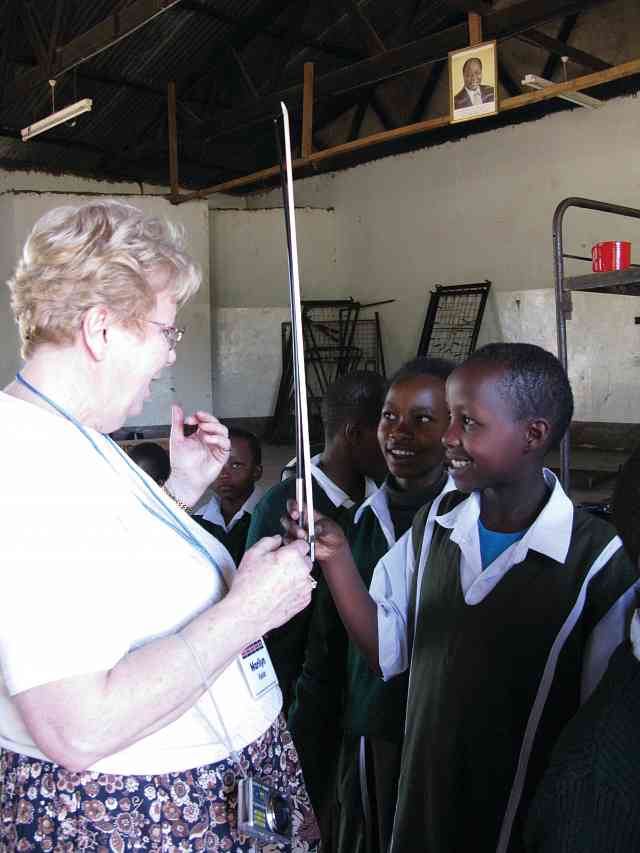

Marilyn Kesler works with students

It will be difficult to keep the momentum going, however, without continued outside support for several years. Dittmar is organizing more trips, said Yun. Logistical challenges the group anticipates are keeping up with the demand for larger size violins as the children grow and continuing to supply quality accessories such as strings. One of Yun’s goals this summer is to work more with Boniface on all aspects of teaching, including proper violin maintenance. “Those will be our challenges in the future, but I don’t think they’re insurmountable by any means,” she said. “I think that’s the exciting part, is building that relationship and having more people going over there and getting involved with the program.”

At the end of the final concert program, Bishop Imathiu stood up and said, “Do you see how wonderful this is? You can do this. You need to dream big.”

“I felt overall that I had gone to Kenya an educator, and I came home educated,” said Schoelles.

Engaging in this type of outreach has made one lesson clear to all the teachers: spreading the joy of music does make the world a smaller, brighter, and more hopeful place.

For more information, photos, and videos from the trip, see Andrea Yun’s blog at http://andreayun.wordpress.com

For more information on KUEF and ways to help or to contact Larry Dittmar, see www.kuef.org