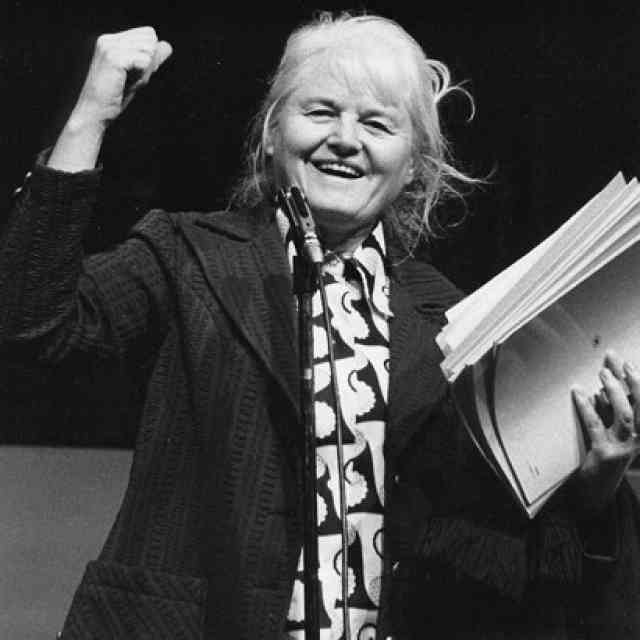

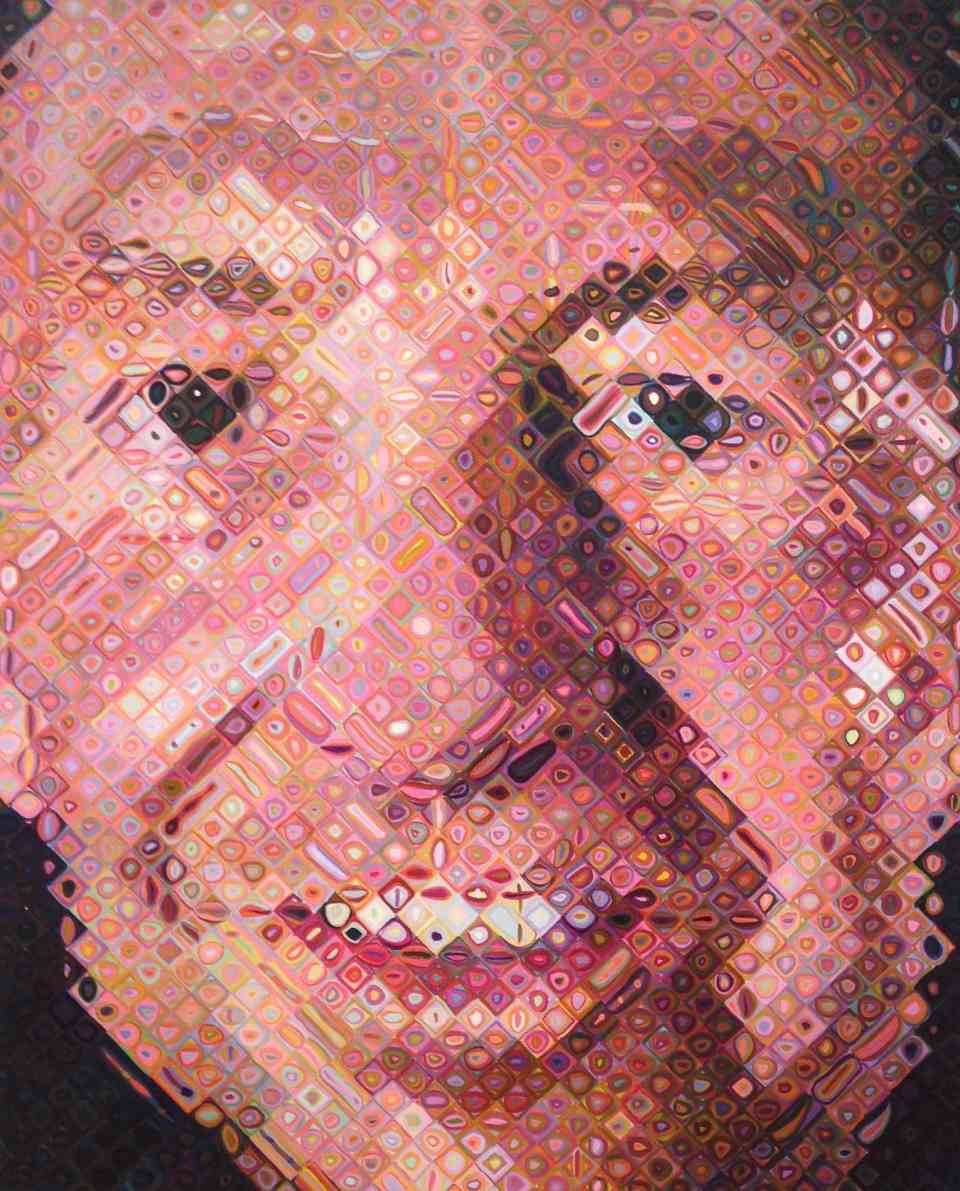

When standing two feet away from Chuck Close’s painting Robert (1997), all you can see are squares and rectangles emblazoned with color. Each square is about three-and-a-half inches wide and linked to another. The colors are richly saturated. Bright borders house circles and shapes inside. The circles remind me of something from my biology textbook, and I envision little colored amoeba, frustrated by their perpetual confinement.

This painting is part of the collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. After viewing the painting on a docent tour, I snapped a few iPhone photos and left curious. I started to wonder why Chuck Close paints these squares. An idea emerged. I began to see a story—the story of one man’s approach to artistic endeavor.

The “doughnut”—a square with a circle inside.

In an archived interview on the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s website, Mr. Close discusses how he paints. He says, “I build a painting by putting little marks together—some look like hot dogs, some like doughnuts.” This commonplace description surprises me. In my mind, the creation of artistic masterpieces is enigmatic. Yet Mr. Close articulates a simple description of his work. He puts “little marks together” and uses familiar, even mundane terms, like “hot dogs” and “doughnuts” to describe his art.

Close begins his paintings with an enlarged photograph of his intended subject. The photograph is overlaid with a grid, and the squares on the photograph become the pixel basis for the painting. The squares are linked together over this grid pattern. Sometimes, two of the squares meld together to create a rectangle. The completed canvas almost resembles a giant piece of colored-in engineering graph paper. At this point in his career, this grid approach exhibits his unique artistic signature.

The “hotdog.”

This style has been partially influenced by Mr. Close’s past. In another video interview on the museum’s website, he describes growing up with dyslexia. As a student, Mr. Close was often overwhelmed by the size of a whole task. He attributes these learning challenges as an influencing factor in the development of his style. The squares demonstrate a visual division of the canvas into manageable parts. He states that the artist has to “solve this little piece, and then you solve that little piece,” working in ‘’small bite-sized chunks.”

Squares linked together over a diagonal grid.

Chuck Close’s work, both as process and product, speaks to the craft of being artists in any field. As a cellist, I find that I can get overwhelmed when I look at the entire whole of a project. Learning a piece of music can be daunting. The musical blank canvas can be overwhelming. I can find myself discouraged by the vastness of the artistic journey, not even sure how to begin. I want to create beautiful things, epic things. But I can also get stuck.

Chuck Close, a successful, active artist, has developed a way to work beyond being overwhelmed. Mr. Close tackles and solves one small piece, one problem at a time. And he does that everyday. He trusts the process of the work. He also balances the tension of working in the present small space (three-and-a-half inches to be exact), while maintaining the vision of the entire whole. At this point in his career, he knows how something entirely magnificent and beautiful emerges out of those squares of color. So, he paints squares and puts little marks together.

I have started to view my practice as an opportunity to create small and seemingly uneventful “squares.” As a cellist and artist, what if I decided to press into the incremental steps, and trusted the process? A fifteen minute chunk of time is an opportunity to create a vividly colored hot dog or doughnut, solving one small problem. That close proximity, that dailiness, is not glamorous. It’s gritty. It may not look like much on any given day.

When it comes to our work, whether we are artists, teachers guiding young artists, or parents practicing with young artists, most of the time we are forced to be working in the squares. These squares are exactly where progress happens, in those incremental steps. Sometimes, I am frustrated by this reality. Just like standing a foot away from a Chuck Close painting, proximity to the right kind of incremental work may not resemble the large scale masterpiece. Maybe I made something that looks like a hot dog; it’s not the project I envision, it’s not the beautiful thing I desire to create. Maybe it’s just a few sentences written of an article, some notes of an envisioned composition jotted down, a measure learned of a new piece of music.

We want masterpieces to come quickly and easily, not over many days, weeks, months, and even years. But when you string many small and thoughtful pieces of work together over a long period of time, you get the benefit and beauty of the increment. Yes, it is vitally important to maintain the vision of the whole, the entire canvas. Yet we cannot demand that the individual parts reflect miniature versions of the whole.

Perhaps we can approach our work with the intent of making a musical equivalent to Chuck Close’s doughnut-like square. We can do the work of solving this little problem, then that one. Tomorrow, we can link two squares together. Those squares start to add up. As we fill the canvas of our work with one small square at a time, we slowly make progress. These squares, they are parts, and they are progress. Someday, they may be part of your story, showing artistic endeavor turned masterpiece.

Robert (1997) Chuck Close

Photo’s of Chuck Close’s Robert by Kathleen Bowman. Used with permission of the Pace Gallery.