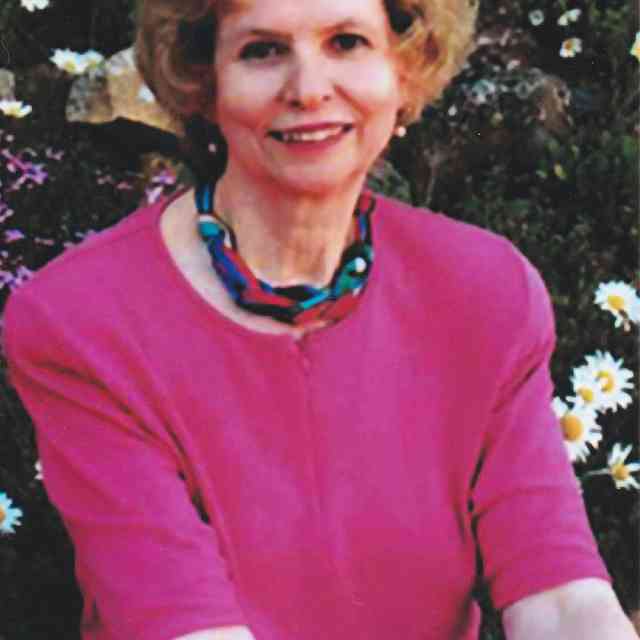

Louise Behrend

It is with great sadness we share with you the news that The School for Strings’ founder, Louise Behrend, has passed away. Miss Behrend was one of the pioneer musicians who introduced the educational philosophy and teaching concepts of the violinist Shinichi Suzuki to the United States.

In the fall of 1970, she started a small Suzuki program in Manhattan, a rigorous course for training Suzuki teachers and an oasis for nurturing young children in the art of music. Within three years, that program had expanded and developed into what is today The School for Strings.

A teacher and musician of great perception, Miss Behrend was widely admired by her colleagues and revered by her students. Her teaching was noted for its emphasis on beauty and variety of tone, serving the expressive and communicative values of music. Painstaking in her attention to detail, she gave her students a thorough grounding in technical control of the instrument, and deep insight into the music’s emotional and intellectual qualities. Unusual in the field, she was an effective teacher at all levels, from the three-year-old beginner to the post-graduate professional.

Louise Behrend received her formal music education at The Juilliard School, in the violin studio of Louis Persinger, an esteemed pedagogue whose students included Isaac Stern, Ruggiero Ricci, and Yehudi Menuhin. Soon after finishing her studies, she was invited to join Juilliard’s Pre-College Violin and Chamber Music faculties, a tenure that continued for more than sixty years.

Her career in performing and teaching spanned more than seventy years. Her contributions to music education received both national and international recognition. In 1989, she was honored by the InterSchool Orchestras of New York at Alice Tully Hall, Lincoln Center, as the recipient of their second Annual Achievement Award. In 1992, she became the first teacher whose students won the Grand Prize in both the Pre-College and Pre-Professional Divisions of that year’s ASTA National Competition. ASTA honored her in 1994 with its Distinguished Service Award.

In 2003, Miss Behrend was presented with the Betty Allen Award by the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, in recognition of her life-long dedication and distinguished contribution to music education in the area of chamber music. In 2007, she received the Paul Rolland Lifetime Achievement Award from the New England Conservatory.

The Suzuki Association of the Americas recognized Miss Behrend in 1996 with its Distinguished Service Award, and in 2002, the SAA gave special recognition to her contribution to the field of music education with the Creating Learning Community Award. Miss Behrend was the subject of a feature cover story in the summer 1993 issue of the American Suzuki Journal. Written in the form of an interview by Allen Lieb, it recounts the story of her life in her own words.

Born in Washington, DC, Miss Behrend lived her entire adult life in Manhattan, returning to the Washington area in 2009 when she retired from teaching. She passed away on August 3, 2011, exactly two month shy of her ninety-fifth birthday.

Her love of the violin, contagious enthusiasm for music and teaching, and her unshakable belief in every child’s potential are at the heart of the legacy she leaves behind at The School for Strings. We are fortunate to inherit her spirit and to be entrusted with her vision, so deeply affected by the work of Dr. Suzuki. She will be sorely missed by all.

Louise Behrend: An Informal Memoir

By Sheila Keats

She was a very special lady.

And it was my great good fortune to know her very well, and for a very long time.

Our friendship spanned almost sixty years, and over the course of time developed into a close working relationship as well. I remember, way back now, sitting with Louise when Dr. Suzuki brought his tour group to perform at Juilliard in 1964. And I remember how impressed she was with what she heard. “I’m a pretty good teacher of children,” she said. “But this man is so much better than I. I must find out more about what he is doing, and how he does it.” And, characteristically, she began making plans for a Far Eastern concert tour which would culminate in a two-week visit to Matsumoto. The tour took place in the summer of 1965. Before she came home, she had spent two intensive weeks observing Suzuki’s lessons, day after day, and at the end of each day discussing the day’s teaching as well as his overall philosophy of education and his many detailed ideas for teaching the violin.

She came home to experiment with Suzuki’s ideas and, through the Suzuki Program she founded in 1970, with 20 children and three apprentice teachers-in-training, became one of this country’s Suzuki pioneers, one of that sterling group which introduced and promoted Suzuki’s ideas throughout the United States. And that little Suzuki Program rapidly grew and grew until, in short order, it became The School for Strings.

As her associate director, I ran The School for Strings for her. I was the second in command, the one who made Louise’s ideas happen. Working so closely together and being, to a casual glance, somewhat similar in appearance, we periodically ran into identity problems. I cannot tell you how many times someone would approach me in the School, greet me as “Miss Behrend,” and start talking. I would have to interrupt gently to explain: “No, no. I’m not Miss Behrend. I’m the Other Lady.”

Louise always chuckled at the recollection of the day, in the early years of the School, when we decided to observe the beginners’ Twinkle class. Arriving before the class started, we sat down on the piano bench to wait. Pretty soon the children began coming in, taking their places on the floor and unpacking their violins. When several had already arrived, a little boy of about four walked in. He looked at us, and his eyes grew wide in disbelief. “Oh,” he said. “Oh, there are TWO of them.” (!)

Yes, there were indeed two of us, but there was only one Louise.

In her quiet, unassuming manner, she led the way, always pleasant, but always persistent. She had a vision, she had a goal, and she never lost sight of it. Very simply, it was to give the best possible musical and violinistic education to as many children and as many teacher trainees as possible. Her own twin passions were music and the violin, and she was totally dedicated to teaching.

I also worked with her as her Juilliard studio accompanist for some thirty-seven years. Lessons with Louise were always lively, always interesting, often exciting, often amusing, often inspiring—and often all of the above. Her gift for words, and her dramatic talent regularly came into play. The eight-year-old having trouble with a tricky spot in the Veracini Gigue: Louise began singing softly, “Use a lit-tle bow, use a lit-tle bow, use a lit-tle bow.” Technical and musical problems solved. The fourteen-year-old who hadn’t quite grasped the essential Spanish character for the Lalo Symphonie Espagnole: there was Louise, one hand on her hip, her head thrown back as she looked over her shoulder, a come-hither look in her eye indicating she was no better than she ought to be—Carmen in person. And the twelve-year-old having trouble with the Slavic character of the Kabalevsky Concerto’s second theme: Louise started singing to that theme what we were sure must have been an authentic Russian folk song, complete with a text in a Russian language of Louise’s own making.

All problems, however, were not necessarily susceptible to instant solutions. Louise was capable of spending an entire lesson on one phrase. (“Not untypical,” as Mark Steinberg commented when I mentioned this to him.) In fact, the students used to place bets with me: would they or wouldn’t they get beyond the opening cadenzas, or even the first cadenza of the Bruch Concerto, the opening Adagio, or even the opening three notes of the Mozart A-Major Concerto, before the end of the lesson? These, plus the Lalo, the Saint-Saens, the Mendelssohn, the Tchaikovsky—you name it—all of them with problematic openings. She used to quote her mother in German: “All beginnings are difficult.” And so, come to think of it, are all middles and all endings.

Her teaching took the student from the initial stage of building a reliable technique and an understanding the musical values of the pieces studied, into the realm of artistry. She spent endless time exploring tone, endless time shaping a phrase, endless time on the quality and variety of vibrato, endless time on just the right, inevitable rubato. Every note was important to her; no detail was overlooked.

Louise could, on occasion, exhibit a wry sense of humor. There was the New York Philharmonic performance of the Brahms d-minor Piano Concerto with Glenn Gould as soloist, the performance for which Leonard Bernstein disclaimed all musical responsibility. By the time Gould was well into the last movement, which was unrecognizable to me, I leaned over to Louise and whispered: “What does he think he’s doing?” “Sh,” she replied gravely, “he is bringing out the inner voices.”

She was a kind, a wise, and a tolerant person. She accepted other people as they were, and was extremely easy to get along with.

She knew good food and fine wine, and enjoyed celebrating special occasions with dinner in one of New York’s four-star restaurants. She loved mountains and mountain climbing and became quite an expert climber. She was also a life-long “cat person,” and always maintained a family of cats in her apartment.

She enjoyed reading and enjoyed traveling, but never had any desire for leisure.

For Louise, to be alive was to work, and to work meant to study music, to practice, to teach, to engage in a continuous search for the beauty and meaning of each piece of music, and each note played on the violin, and for a better way to teach and reveal these. In this, and in her unselfish desire to share her own knowledge and joy in music with as many others as possible, she had much in common with Dr. Suzuki, whose ideas and ideals she blended into her own for a remarkable life. Innumerable people, including me, have said that she changed their lives. And so she did.

She was truly a very special lady.

Recollections

Louise Behrend taught me the joy of learning how to learn. Although I went on to study with other remarkably sage and wonderful people after her, if you ever hear me say “my teacher,” it is she to whom I refer.

In so many lessons Miss Behrend would tell me of some new discovery she had made while practicing in the past few days: if you feel this finger just so on the bow you might hear just this subtle reflection of it in the sound. As a kid, hearing that your beloved and revered teacher is still discovering things, still figuring things out, is a potent realization. We were always searching for just this or that shading of a sound, some special, poetic shaping of a note. We spoke of and listened toward the inner life of a sound, explored the inner sensitivities of the fingers. Heady stuff for a young man. Often months went by when I couldn’t fathom what she was after, and yet she managed to keep me engaged. On occasion her eyes would brighten, and she’d say, “That’s it! Did you hear it?” Too often, I’d sheepishly have to answer, “Um, no.” There was never a feeling that I had disappointed her. Instead, we’d start again, listen again, become more attuned to what was happening. The process of questioning and of magnifying the musical elements so that together we could enter the piece from the inside and learn how to illuminate it, how to make it glow and sing and speak and dance, was tremendously exciting. It was the process that Miss Behrend put the most focus on, in her endlessly nurturing, supportive cajoling and insisting. And insist she did. An entire lesson on shaping the first note of the Bruch g-minor Concerto, one on the attempt to get the sound to blossom through the first three notes of the Mozart A-Major Concerto, countless lessons on the theme of the Bach Chaconne, balancing chord against chord and finding the rhythmic propulsion of each element. Then there were the etudes, a year of work on Kreutzer No. 2 with its seemingly infinite variations, and so on. I ask myself now, how is it possible that I have no memory of being perpetually frustrated at the pace of the work, at the high standard I failed to reach time after time? Maybe it’s because as long as I was working, as long as I was engaging my curiosity and my powers of perception, I was in fact reaching the standard. Because there was no end in sight, and Miss Behrend lifted my eyes toward the horizon again and again.

When I graduated from high school, Miss Behrend gave me a gift certificate from Tower Records to mark the event. The certificate and store are both now gone, but the envelope it came in still resides in my violin case. On it she wrote “for Mark, with love and my conviction that you will be a great artist some day.” I treasure that envelope and still aspire to live to that day. But I can also lose the envelope, because that love and that belief in possibilities are gifts from Miss Behrend that I carry with me always. I thank her every day in the way I know best, by pursuing an engaged life in music, in wondering and in reveling in the beauty of what might be possible, just as she always did.

Thank you, Miss Behrend, You have given me musical life, and you have taught me so much about gratitude, admiration and love.

–Mark Steinberg, former student, founder and first violin, Brentano Quartet

In celebrating the life of Louise Behrend, I leave it to those who are more conversant in the world of Suzuki teaching to determine her impact in that sphere. (Though at the School for Strings’ recent 40th anniversary event at Carnegie Hall, it was palpable to me the moment that hundreds of young string players of all ages launched into Twinkle. All of their teachers had come through SFS’s teacher training program and I was reminded of how wide her reach was.) I studied with Miss Behrend from the ages of six until sixteen, having been brought to her by Doris Rothenberg, one of her early teacher trainees. I think Miss Behrend was defined by the high musical values that she placed on every piece, whether it was Twinkle, Bach’s Double Concerto, Lutoslawski or Sibelius. And in each piece, and in any phrase of any piece, she demanded that you have a sound intention in your head before manifesting it on your instrument. For her, physicality was a means of realizing musical ends, rather than a preset mold in which you poured your students. This ended up meaning that her students look and sound different from each other!

Miss Behrend was thankfully from a generation that was sparing in their compliments. If I thought I really played well at a recital, I might hear, “Not bad,” or, “That’s getting better. Now we have to work on your right hand.” In an era of inflationary rhetoric, when every artist is the most fabulous new thing, every prodigy can play faster and louder than the next, she kept one’s feet on the ground. When I was around elevan, the local ABC news affiliate was doing a special on “prodigies” and I was one of the featured kids. Many teachers would see this as an opportunity to market themselves and their student. However, when Miss Behrend was interviewed, her sense of honesty and distrust of the “prodigy” thing led her to say something typical, like, “He played all right, but we have to work on those false harmonics.”

Towards the end of Miss Behrend’s life, I visited her at her home in Washington, DC, along with Mark Steinberg and Sheila Keats. At that point, she was a little foggy, had trouble remembering things, and ended up repeating questions often. However, as soon as the conversation happened upon an item of bowing technique, she perked up and was completely lucid. I believe the thing that had been brought up was something she called “Feelies.” They were a series of exercises she had invented that enhanced one’s awareness of how the bow is in contact with the string and helped one to pull a very natural sound, never forcing. Miss Behrend was from a family of doctors and scientists, and “Feelies” were one of her many inventions in a life spent constantly searching for new ways to enable her students to make music, to search out a sound in their imaginations and then realize it on their instruments.

Thank you for all you have given me and the world, Miss Behrend!

–Colin Jacobsen, former student, co-founder of the quartet Brooklyn Rider and the chamber orchestra The Knights

One day in the fall of 1998, I told my husband about a violin school in New York called The School for Strings. Our two daughters were five and nearly seven at the time, and had been playing violin in a local Suzuki program in New Jersey since the age of three.

One of the other parents in the New Jersey program, whose older daughter already studied at SFS, told us we had to see the school and its remarkable leader, Louise Behrend. So one Saturday that fall, our older daughter Kate and I spent the day shadowing our friend’s daughter at SFS: orchestra, group class, theory and private lesson, we saw them all. The children seemed enthusiastic and engaged, and Kate thought it was fun.

Soon afterward, we went to a Sunday afternoon open house for prospective students and their parents, and that was when we met Miss Behrend (as everyone invariably called her, no matter how long they had known her) for the first time. We had no clue then that this small, gray-haired dynamo of a woman would be such a significant figure in our daughters’ lives—and ours—for the next ten years and beyond.

Miss Behrend was devoted to children, and she surrounded herself with extraordinary teachers and staff who all were dedicated to the same fundamental principle of Shinichi Suzuki: that every child can learn the language of music. And all of the children at her school did learn that language—regardless of their preexisting levels of aptitude or enthusiasm. Perhaps even more important, each child and each parent immediately felt part of the larger musical world. Each child proudly identified as a violinist—even though still standing in position with only a box under the chin where a violin soon would be—and the same was true for the cellists and pianists.

But Miss Behrend’s commitment to the musical education of all children did not diminish her devotion to high musical standards. Her teaching of technique, and her ability to communicate the ineffable quality of musicality, were unparalleled. When she identified a student with particular potential, she spared no effort to encourage that child to realize it. Even after Kate completed the Suzuki books and went on to study other repertoire, Miss Behrend maintained our Suzuki parental role as “assistant teachers,” and we became her personal friends. We continued to attend private lessons until our daughter begged us to let her go alone, and these were a memorable musical education for us as well. She continued to welcome all her students’ parents to her studio group lessons until the very end of her teaching career—and we learned something new from her every time.

Miss Behrend was an integral part of the tradition of musical hands across the generations. “As my teacher Louis Persinger used to say,” she would tell her teenaged students when discussing the subtleties of a particular passage, and suddenly the old master was in the room with us, explaining through her what he had learned from his own master teachers more than a century ago. Our daughter felt privileged to be able to share in this legacy.

Louise Behrend was an extraordinary and altruistic humanitarian. She was committed to the perpetuation of musical education, and so took care to train teachers as well as students. In the end, she made us see the world through her eyes, and to understand that teaching music to children created not only new generations of musicians and audiences, but also made the world better. She gave us all a priceless gift that will never die.

–Lillian Pliner and Stephen Dreyfuss, parents of former student Kate Dreyfuss

We will always love Miss Behrend and miss her terribly. Our son took lessons with her from the age of seven until the time she retired. From the start, we found her to be an incredible teacher and an extraordinary human being. We came to her as parents with no musical training. She took our son and made him the best musician he could be. She did it with grace, kindness, and an amazing spirit. These qualities will go on in every student she nurtured and will continue to be an inspiration to those fortunate enough to have spent even a short time in her company. Miss Louise Behrend is a legend who lives on in all of our hearts.

–Adele and Victor Ronchetti, parents of former student Victor Ronchetti

I was terribly saddened to receive Sasha’s [Alexander Yudkovsky] e-mail about Miss Behrend and wanted to express my deepest condolences. While I didn’t have a personal relationship with her, the many stories you [Miss Keats] have shared, especially about the early days at SFS, brought her to life and impressed upon me what a passionate, generous, determined, and visionary person she was. Her spirit will be kept alive, of course, through her legacy at SFS and Juilliard, but her bright smile and enthusiastic Twinkling at the violin recitals will be forever missed.

–Linda Kahn, current SFS piano and violin parent

I was saddened to hear about the passing of one of the great pioneers in the Suzuki world. I was one of the first students at The School for Strings. I spent a wonderful six years there before entering the Juilliard Pre-College Division. Many of my fellow students went on to become performers as well as teachers. I feel fortunate giving back what I have learned to many of my own students and those I teach at summer institutes. Louise always had high standards when preparing the students for concerts and that quest for excellence remains a fabric of my teaching philosophy. The reason Suzuki has become such an important staple of early childhood development can be attributed to the vision of Louise Behrend.

May she rest in peace.

–Tal Schifter, former student, director, Suzuki Strings of Long Island

I was introduced to the Suzuki Method while attending Manhattan School of Music. My teacher Miss Behrend announced one day, “Why don’t you take my Suzuki teacher-training class?” I knew nothing about the Suzuki method but was sold on it the first ten minutes of the orientation class. What I remember most about Miss Behrend was her magic of making me always feel like her equal, her never-ending persistence to bring life to the music, and the many, many, many, one measure per hour lessons. In my mid-thirties, Miss Behrend said to me, “You know, Sherry, you can call me Louise.” I tried, but I never felt comfortable since she was my teacher and I was still learning from her. Miss Behrend is a large part of who I am today as a teacher and person. I will miss her greatly.

–Sherry Cadow, former student, Suzuki Violin Teacher Trainer, Colburn School